NON-FICTION BOOK

by Jack Fritscher

How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

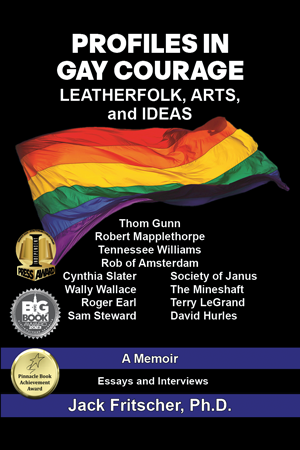

PROFILES IN GAY COURAGE

Leatherfolk, Arts, and Ideas

Volume 1

by Jack Fritscher, PhD

WALLY WALLACE

1938-1999

The Mineshaft

October 8, 1976-November 7, 1985

Wally Wallace Tells All

Performance Art, Gay Space, Mapplethorpe,

AIDS Disruption, and the Provocative Film Cruising

Wally Wallace founded and managed the Mafia-owned Mineshaft at 835 Washington Street in the Meatpacking District in New York City where the club ran nine years and nine days: October 8, 1976, to November 7, 1985. While his eyewitness memories were still fresh, I interviewed him for nearly three hours on March 28, 1990, when he sat for my video camera in the attic at 206 Texas Street where he stayed on his visit to San Francisco. When the interview ended, he opened a small suitcase and gave me eighty priceless photos snapped inside the Mineshaft. Our relationship was fourteen years old. We had first met around the opening of the Mineshaft, and he remembered me as the first national journalist to write about it. Having promised to publish his story, I wrote the very detailed “Mineshaft” chapter in the leather history book Gay San Francisco: Eyewitness Drummer. What follows is my transcription of Wally’s exact spoken words lightly edited for flow and clarity.

START VIDEOTAPE #1

TIMECODE: 01.00

Jack Fritscher: Please tell me about yourself as background for how you managed the Mineshaft.

Wally Wallace: As long as I can remember, I was on stage in plays. As a kid I had a lot of fantasies and was left on my own a lot. I was born May 12, 1938 [died September 7, 1999], during the Depression and grew up during the war years. We lived in the suburbs of New York. My dad worked for the government. My weekends were spent in the city at my grandmother’s house, a big sprawling West Side apartment which I sort of roamed in. I played games by myself: hide and seek, games like that. I was sort of an introvert with a lot of fantasies. Later I got involved with theater.

Jack Fritscher: So you enjoyed a “fantasy theater” boyhood.

Wally Wallace: Sort of like cowboys and Indians. I always enjoyed the men in the movies more than the women. Before the Mineshaft, I worked at a bar called the Ramp. I also worked for JC Penney developing their early mail-order catalog, sort of production manager. At the same time, I did a lot of theater in New York.

Jack Fritscher: Yes. Weren’t you part of La MaMa [Experimental Theatre Club]?

Wally Wallace: Oh, yeah. Mainly in small parts. I did a lot of lighting too. Stage manager. That sort of thing. We opened La MaMa in three different locations because the police kept shutting us down or the rent would go up and we’d have to move somewhere else. Of course, now, La MaMa is long lasting and has done very well. At the same time, I was involved in day-to-day operations, public relations, etc. I was making travelogue films at one point, directing, writing scripts. After I got out of the army in 1963, I moved into New York [into an apartment] that an army buddy of mine was vacating. Got my first job. Of course, in those days one could afford to live in New York with a rent-controlled apartment.

In about March of 1976, Terry McNulty, a friend of mine, a club brother, founder of a small [gay leather biker] club called “Excelsior M. C. [Excelsior Motorcycle Club]” — still around — was managing a bar on 18th Street near the highway called the Ramp. He wanted to go into the clothing business, leather goods. So I said I would try managing the bar. I knew a lot of people, used to give a lot of parties. I thought I would just be a bartender, but soon it became too busy for that. The place really took off. It was a couple blocks from the Spike and the Eagle. It was the upper floor, and it had kind of a game room. We cleaned up the rest of the deserted building and expanded the bar. It became the most popular backroom bar in the city, and also kind of a “leather bar” that summer. The people [the Mafia] that I worked for weren’t too nice. That’s the best way of putting it. As it made more money, instead of bringing in the people that I wanted, they brought in their own bartenders. Then they lost their license. So I left.

Then somebody called about this disco place in the neighborhood called the Mineshaft. It was called that before I took it over. It had been through several semi-legal incarnations: one was a leather bar called the Den; another was the Zodiac.

So, in 1976, this disco place called the Mineshaft was running concurrently with the Ramp, but it wasn’t doing very well. Michael Fesco’s Flamingo was the place to go for disco fans.

Jack Fritscher: How is Michael Fesco? We had an intense four-day affairette in San Francisco during Jonestown weekend in 1978, the week before Harvey Milk was shot.

[Michael Fesco (1934-2019) was a drop-dead-hot-and-handsome Broadway dancer and cultural influencer of New York nightlife whose pioneer disco enterprises from his Ice Palace on Fire Island (1969-1974) to his Flamingo disco (1974-1981) to his “Sunday Tea at Studio 54” (1981-1984) to his Sea Tea gay party cruises (1997-to his death) around Manhattan gave seminal soul to gay popular culture and made the always hale and hearty impresario a beloved figure.]

Wally Wallace: He’s still around. He runs a tea dance on Sundays at a place called 20/20 (opened 1988) at 20 W. 20th Street. A nice space.

So I left the Ramp. There are things about the Ramp that are very special to me personally. It was my first endeavor in taking a space and utilizing it in my way. The Ramp was a safe space in the sense that we had the [Christopher Street] piers going at the time and we had the trucks. The actual piers and docks were not safe places for guys trying to have a good time and sex. There were murders and things like that. So by bringing sex indoors, I made it safe. This was the success of the Ramp.

I was then offered a position running a club at the Mineshaft. I had been there a couple of times but didn’t really like it. It didn’t seem to be successful and there were a lot of underage kids there. I said, “The only way I can do this is completely close it down, take a few weeks, spend about $500, and turn it into a leather bar.” I sent out a mailing. Here’s a copy of it. This was in the fall of 1976 when it opened. When I first looked at it, my intention was to change the name because it had this bad reputation, but when I went to see it, first of all you entered through some stairs and you went to a second floor and the operation at that time was all on the second floor where there was a bar and a pool table. I remember a false ceiling with white florescent lights and when it was lit up, it looked like a butcher shop [like the butcher shops on the same loading dock as the entrance to the Mineshaft].

To the right there was a hallway, then another big room which was the dance floor. In the middle of the floor was a box which they used as a small stage for go-go boys to dance on top of. I said, “I have other uses for this room. It should be a backroom because that’s what people want these days.” The owners agreed. I said, “I want to move this box,” and I discovered the box was on top of a door. A metal trapdoor. I said, “What’s this for?” They said, “It goes downstairs to an old freezer.” So I opened up the door, went down a flight of stairs, and then realized that we were on the street-level floor where there was a big meat freezer with drains. I remembered seeing a place. It was in San Francisco, a place called the Barracks on Folsom Street. I had only been to San Francisco once at this point. I saw somebody was in the bathtub at the Barracks, which I thought was very hot.

Jack Fritscher: The Barracks was the hottest place in San Francisco next to the Slot.

[The Folsom Street Barracks South of Market was a post-1906-quake corner building whose street entry was at 72 Hallam — with a second entrance into the bath itself through the Barracks’ Red Star Saloon in the front corner of the same building at 1145 Folsom Street. It was a four-story former skidrow single-occupancy hotel for working men that changed to a bath when it opened May 15, 1972. It quickly became an S&M orgy scene and dream destination for locals and for sex tourists who could spend entire vacations enjoying private rooms, lockers, sauna, continental breakfasts and lunch in the bar, and thousands of international men in towels and leather treading the carpeted halls, showers, and orgy rooms. Its poster suggested: “Stay a night, or a weekend, or as long as you want!” I reserved the same room, 326, first door to the left at the top of the stairs, every third weekend and every New Year’s Eve beginning in May 1972 when the Barracks set the bar for what a kinky gay play space should be. Wally Wallace distilled that inspiring essence for his Mineshaft. On July 11, 1981, an arsonist destroyed the Barracks that had been closed for remodeling in the worst fire San Francisco had seen since the 1906 earthquake.]

Wally Wallace: It had a bathtub, where somebody was in the bathtub, fully clothed, getting soaked with piss, surrounded by a big crowd pushing in to piss on him, which I thought was even more hot.

Jack Fritscher: So you put a bathtub on the ground-level floor of the Mineshaft.

Wally Wallace: That bathtub became famous. I didn’t realize how many people were into bathtubs.

Jack Fritscher: Into piss…

Wally Wallace: Ha! The point is, I kept the name of the Mineshaft, because I had found an actual shaft under this metal door which went to the lower level.

It was also safe. Over the first year, the Mineshaft went through a lot of problems with police and building codes, etc. But one thing about the space was it was totally safe because the lower level, which always seemed subterranean, was actually on street level. By the time it closed, the Mineshaft had five exits, three with double doors, to the street. In that sense, it was perfectly safe. In time, we had to put in a water sprinkler system. We had to do so much for building codes, etc., probably harassed to the point that… But we were probably the safest place in the Village. About six months after we started, there was a terrible fire at the Everard Baths. Several people were killed. [On May 25, 1977, nine men died.] When the Metropolitan Community Church went to find out which places were safe in terms of discos, etc. to host an Everard benefit they were putting on, our papers happened to be on the desk of a local fire marshal, having just gone through an inspection. So the benefit that was done for the fire victims was put on at the Mineshaft. There was just a fire last week where 83 people were killed at a social club in the Bronx. That would never have happened in the Mineshaft.

Jack Fritscher: So you were practicing “safe sex” from the get-go.

Wally Wallace: Our building was safe, but the sex definitely wasn’t. AIDS was still in the unforeseeable future.

Jack Fritscher: What was the dominant sexual activity at the Mineshaft? It seemed, “Anything goes.”

Wally Wallace: The most basic thing was cocksucking, then fucking, then fisting, then other things. Oh, rimming. And a lot of tit play. S&M. You know, you start at the top and go to the bottom.

Jack Fritscher: That’s gay sex to a T.

Wally Wallace: Before AIDS, there were a good four or five years when people were pretty wild and abandoned. They did almost anything they wanted.

Jack Fritscher: That was the Seventies. How did you change the image from the disco?

Wally Wallace: We were closed for a couple of weeks. So I went to a mailing list. It was a private club from the beginning. A men’s club plus a couple of women. The night of the opening, the word had got out through my newsletter; but then also just word of mouth. People were looking for something different. The Eagle and the Spike, which were the leather bars at the time and still are today, had become rather inundated with other people who were just out slumming and not into the leather scene. So people were looking for a new place to go. I promised a dress code, although at the time I didn’t know what it would be. It was to be a membership club.

Well, the first night we opened! We were on the second floor. I was standing at the entrance greeting friends, etc. Then I noticed an attractive female standing halfway up the stairs. I said to her, “I’m sorry, but you can’t come in here. This is a men’s club, a gay men’s club. It might be embarrassing for a woman.”

Jack Fritscher: I know this story. I love this story. It’s canonical. She herself told me.

Wally Wallace: She said, “Well, I go to the Spike and the Eagle.” She was dressed in leather and a very attractive girl. I said, “I’m sorry, but we determined that this was to be a private club for leathermen.” I was worried about getting into trouble with women’s rights groups. We had had some trouble at the Ramp with women trying to get into the backroom, but that was a public bar. But when she left, all these hot men standing on the stairs also left with her. So I said to myself, “I’ve got to find out who this woman is.”

So I made inquiries to find out who she was, and that’s how I met Camille O’Grady.

[Camille O’Grady (c. 1950-2020), my longtime friend, a brilliant mind, a great beauty, flawless skin, raven-haired, Irish-American from New Jersey, Pratt student, punk poet/artist/singer who identified as a “gay man in a woman’s body,” toured with Lou Reed, dated Robert Mapplethorpe, performed at CBGB before Patti Smith, and was nearly murdered when her lover Academy Awards Streaker Robert Opel was shot standing next to her (with a shotgun held at her throat) in their Fey-Way Gallery in San Francisco in 1979. Having been ill for years, she died of unannounced causes in the Coming Home Hospice in the Castro at 115 Diamond Street on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 2020, two weeks into the first Covid lockdown.]

Camille became our sort of token female member of the Mineshaft; but she could only go to the bar area, and she couldn’t bring any of her women friends, which she didn’t. She pretty well stuck to those rules. I know that sometimes when I wasn’t there, she would end up in the backroom; but I wasn’t supposed to know. I’m sure she got involved in some pretty hot scenes. Lots of other people — men as well as women — who bragged they made it into the Mineshaft were lying.

There was another bar running nearby called the Anvil [owned by my friends and playmates leathermen Frank Olson and Don Morrison]. The Anvil had staged sex shows. Guys would get on the stage and be fisted, and there were stories of various female celebrities who would go there. [Jerry Torres, the star of the Maysles documentary, Grey Gardens, once took Jackie Kennedy Onassis to the Anvil.] And the guys on the stage: one was named Toby Ross [not gay film director Toby Ross], and he could take anything and he did. So there was a place for other people to go. The Anvil was a little bit of everything. In time, it became more of a drag bar. In the beginning it was a leather bar. They had backrooms too, but we never paid anybody to do anything or to perform.

I always felt the Mineshaft was like a gay man’s bedroom. In a city like New York, you had a lot of people living in very small accommodations at that time. Single rooms, very small apartments with doormen. Guys went to the baths to have their sexual fun. They also knew it was safe in the sense that whoever they carried on with was not going to rip them off or whatever. We did have a number of pickpocket problems, which I think we controlled rather well. We were concerned about it. A lot of clubs didn’t even care. There was a place called the Toilet which used to hire their own pickpockets to work the house. This is true. That place went out of business in our second year.

Jack Fritscher: When did you know you were a solid hit? How long did it take?

Wally Wallace: Wasn’t long. We opened in October and by December. Hmm. It didn’t take that long. I’m sorry I’m very bad on chronology. But the Mineshaft was always more than just me. I was very fortunate to have some very good guys working for me. Like any place there are those who work with you, those who work for you, and then there are those from the day you hire them are working against you or want to change things to their own. There was one particular incident I remember in the early days. The Ramp as I mentioned also had a backroom. There was a very big celebrity who used to go to the Ramp.

Jack Fritscher: For the record, who was it?

Wally Wallace: Rudolf Nureyev used to come to the Ramp and play there. And he loved to create scenes. He was an exhibitionist, a performer, but in a different way than on the ballet stage. When he went off to make the movie Valentino [directed by Larry Kramer’s friend Ken Russell; released 1977], he stopped at the Ramp. It was a very dead night, maybe Tuesday or Wednesday, and he had this chauffeured limo stop at the Ramp so he could make his farewells. And I think it was something like $1 to go upstairs at the Ramp. There was an extra charge if you wanted to go upstairs to play around.

At the Mineshaft we had something like a $3 door charge. It was never very much. So one day Nureyev came to the Mineshaft when I wasn’t there, and we had a French-Canadian fellow working for us who felt it was his job to enforce the dress code to the nth degree. Because Nureyev had on a long fur coat, he was refused admission. So he took off his coat and was in full leather, but the doorman wouldn’t let him in because he still had the fur coat with him and this arrogant son of a gun who worked for me wouldn’t even check the coat! Nureyev vowed never to come back, and he never did. I never had a chance to talk to him personally. We gave him his privacy when he was there. Obviously, the French-Canadian kid didn’t stay there very long. He had an attitude.

The dress code at the beginning was basically leather or Levi’s. In those days leather was sub rosa. You didn’t talk about S&M which, of course, was connected to leather. But after a while, we decided to have a meeting of the members. The only reason for making it a membership club was to keep open later than the official closing time for public bars, which was 4 AM every night except for 3 AM on Saturday night. Beyond that, you had to be a private club. At that time, nobody who had a private club bothered about getting a liquor license in New York City. There were hundreds of social clubs, some still to this day. I mentioned the Bronx fire.

Anyway, we had a membership meeting to decide on a dress code. It was packed. I presided and we appointed a secretary. Interesting things were brought up, but the number one thing that irritated people, and the specific thing that they wanted in this dress code, was no perfume, cologne, scent, etc. Of course, everybody wanted people to smell like sweat. People appreciated the “natural” scent. Then some people wanted the dress code to be totally leather. I pointed out that the business could not exist if it was just leather. One thing was a lot of the young guys couldn’t afford leather, and we definitely wanted guys to be naked if that was their thing. Because of the New York fire code, people always had to have their shoes on.

We would allow jockstraps, raunch wear, torn T-shirts, that sort of thing — anything that would make a guy look or feel sexy. We would not allow dress shirts and ties, suits, dress pants, sweaters. That was a big thing. People should not wear sweaters in leather bars, even though there is a hot military sweater. In the early days, in time, as the uniform clubs evolved, there were things like military tights and sweaters we could allow. “No turtlenecks,” I think I said. How can you get the guy’s tits when he’s got a turtleneck on?

A lot of things like this came out of this meeting. The thing I did allow was sneakers. If they were too white, of course, we had to do something about that. We dirtied them up. Technically sneakers were never against the dress code, but people thought they were [likely because Chuck Arnett’s Tool Box bar (1961-1971) in San Francisco had a sign made famous in Life magazine in 1964, saying “No Sneakers Allowed”]. Even then, some members would sometimes say something about the color of sneakers, red or yellow, maybe, but I had nothing against the basic sneaker.

Jack Fritscher: When did the Mineshaft take on its character of being more than just a backroom, into being, well, “Grand Opera”?

Wally Wallace: I don’t know exactly what you mean by “Grand Opera”?

Jack Fritscher: I mean a sort of way larger-than-life Living Theater with no fourth wall like Julian Beck in The Brig or Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty where your members could act out so many spectacular high-performance scenes in so many different stage sets with a cast of thousands.

Wally Wallace: The secret was the space itself. In time, we expanded the space to accommodate the sex and the crowds. I mentioned that we had found under that go-go box an actual shaft that had a wood-frame stairway where you could go downstairs, and there was a tub down there. The exact dimensions of the building I don’t really know offhand, but it wasn’t as large as it seemed to be. It was about a half-block long, but New York City blocks are like alley blocks elsewhere. They’re really not that long. And it was relatively narrow. In time, we took over the entire street floor, which had included the Den.

The Den was at one time a straight bar in that building which for some reason went out of business — tax problems or something. When we moved in, well, let me say first of all, the Mineshaft is in the middle of the Meatpacking District, and, at that time, with all the meatpacking firms, there were a lot of straight truckers who wouldn’t be caught dead going into the Mineshaft. But there were three places in the neighborhood where straight guys would go in and watch strippers, go-go dancers, naked women, that sort of thing, and drink beer or whatever. The Den had become one of these places, kind of a club. When there was a crackdown on that sort of club, the space became vacant, and then we took that over. The other part of the building — the northern part — was some sort of a carpenter shop. Eventually, we got that too. So we had the whole building. The owners of the Mineshaft did not own the building, but rented it from someone. I think from lawyers. The Mineshaft became very notorious when — I can’t remember the year. When was Cruising made?

Jack Fritscher: It was shot in summer 1979 and released in 1980.

Wally Wallace: Because that was a crucial time. A lot of things changed then, which we should probably talk about. Anyway, what happened was the lawyers or agents for the owners of the building represented an estate, and it turned out that the beneficiaries of the estate were underage kids getting a trust fund. So when the movie Cruising came out, the owners of the building offered to sell it to the Mineshaft owners. Cruising was not filmed at the Mineshaft, but it did give us notoriety.

Jack Fritscher: Let’s sort this out. The Mineshaft had gained a certain notoriety well before Cruising.

Wally Wallace: Right. Certainly, in the gay scene, it had become the place to go. New York and San Francisco at that time were the hubs of the gay tourist industry for a lot of reasons. They were known as gay cities. Big gay populations. Air fares were low. Europeans’ money went a long way. We had lots of tourists from all over Europe.

One time I had a doorman who for one week kept tabs on where everybody was from who came through our doors. We called it “Seven Days in May,” but it was really ten days over two weekends. I think it was something like thirty-three states of the Union and over forty countries in that period. About the only countries not represented were from behind the Iron Curtain. It was just amazing. I knew a little bit of German from my army days — “G.I. Deutsch” — so I had fun with the Germans. New York is supposed to be this horrible cold city, but we did everything possible not to be that way. I am basically a friendly person. I have trouble with attitude. As long as you’re not hurting someone, do it if it gives you pleasure. So we had guys from all over the world. The Dutch especially were wonderful.

Jack Fritscher: When did you notice that the Mineshaft was getting to be a lot kinkier than you first thought?

Wally Wallace: When did I first think that? Because in the beginning I thought it would be just a basic fuck and suck in the backroom. Well, it was fairly early on that we put up slings. I don’t know exactly. I’m sorry that I didn’t keep a diary, but then if I had…Wow! But we had a good group. The FFA [Fist Fuckers of America] was older than the Mineshaft. You have to realize that for any business, anywhere in the world except maybe in Las Vegas, there are so many dead times during the week. When the Mineshaft opened, there were maybe thirteen leather bike clubs in the city. There was besides the FFA, the T.A.I.L. Chapter [Total Ass Involvement League], and the Interchange [biker club]. A lot of these bike clubs were relatively new. So we tried to attract these clubs in there, for events or whatever to fill the slow nights [like inviting GMSMA — Gay Men’s S&M Association — to run seminars advertised as “The School for Lower Education”].

Jack Fritscher: Promotions.

Wally Wallace: It’s part of the business.

TIMECODE: 51:56

Wally Wallace: I think the slings changed the game. I always had a problem with being fisted, although I tried it, as I’ve tried a lot of things. I was naïve about a lot of things. I missed the drug culture along the way. I was certainly naïve about a lot of the drugs in the gay scene. Unless somebody was so stoned that they were falling over, I was not aware of them being on something. The FFA was a very heavy drug scene — as I finally realized when their orgies went on for days. It took me awhile to realize that some of my staff were addicts. I wasn’t looking the other way, but I wasn’t seeing things as they were.

Jack Fritscher: Do you think it was your wild staff who encouraged wild sex to happen?

Wally Wallace: Oh yes, some of the guys came in with bright ideas for personal fetishes. I had learned at the Ramp, and also as a customer for many years in bars, that the “professional bartender” was not necessarily the person you want behind your bar. First of all, we had a limited drink menu. We didn’t make Zombies or all those cocktail concoctions at the Mineshaft. No name brands. The basic drink of the Mineshaft was beer. We sold a lot of beer. Beer and soda were the basic drinks. Bud and Bud Lite. No Perrier. We got a lot of requests for it, but we had no Perrier. We had house brands. Our drinks were not expensive. Our door entry was maybe $10 towards the end on a Saturday night, otherwise $8. This was for non-members. Members were about half that. We gave out freebies to other bars.

People talk about the sex at the Mineshaft, but sex was not what it was all about. First of all, I had a policy that the music was never so loud that you couldn’t hear the person next to you.

Jack Fritscher: Who created your music tapes? I remember your reel-to-reel tape deck perched behind the bar.

Wally Wallace: I did. I made them. So did Jerry Rice…

Jack Fritscher: Mon amour — for a minute — and houseguest back in 1971. He borrowed my copy of Bill Carney’s leather novel, The Real Thing.

Wally Wallace: …and Michael Fesco and a guy named Ashland. I asked all kinds of people to make new tapes to fit our scene [including Thom Morrison in San Francisco]. We played anything in the world, from western to classics. A lot of classics, actually. Electronic variations on classic themes. Ella Fitzgerald, jazz. Tomita, new wave.

Jack Fritscher: I remember hearing Kitaro, and Kraftwerk’s Trans-Europe Express, and Tim Buckley. His “Sweet Surrender” was more seductive than poppers for fisting.

Wally Wallace: We tried to avoid basic disco, references to females, references to “let’s dance,” things like that. But our music became kind of famous because we didn’t follow the mainstream. We had a somewhat older clientele. When the New York drinking age went up from 18 to 21, the Mineshaft was one of the places least affected by that loss because our guys had generally grown to a point in life where they were old enough to know what they wanted. They knew what kink was. They were single guys. They weren’t out to blind date, nor to emulate the straight world in terms of sexuality, lovers, dogs, and family.

But getting back to the main room at the Mineshaft. It was a very creative space. We had sawdust on the floor. It was a basic western motif. No black walls in the main room. In time, we did have video; but when video got big, we wouldn’t play it all the time. Movies a few nights a week. Porn in the early hours when it was slow, not during the rush, because I figured people weren’t there to watch sex. They were there to do it. I would discuss things with my staff. The one that I was closest to, he was there almost the entire time — our official run, incidentally, from opening to closing, was nine years and nine days. The guy’s name was David Fishman, known as “Butch.” Butch did the matinees. He had another job in the straight life. Worked Saturday and Sunday during the days. On weekends, we were open 2 PM to 10 AM. None of the guys worked more than eight-hour shifts. Other places make their bartenders work twelve-to-fourteen-hour shifts, but I didn’t believe in it. That’s no good.

Jack Fritscher: Let’s talk about size…crowd size.

Wally Wallace: The biggest crowd we ever had was on the night of the circus, an annual benefit by Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus at Madison Square Garden [where the elephants linked trunk to tail come from Long Island into the city parading out of the Queens Midtown Tunnel to the Garden], and we had a party afterwards. That night we did have a lot of women there, but not downstairs.

Jack Fritscher: How many?

Wally Wallace: I don’t know. It wasn’t a normal night. A regular Saturday night would be 500 to 600 guys. On the circus night, there must have been over 1,000. We had a roof — I didn’t mention that. Eventually we opened up the roof, and that was a very popular space up there. Guys could get away from it all up there.

Jack Fritscher: I remember. It was kind of romantic up there with the moon over Manhattan.

Wally Wallace: Yeah, it had a wall around it. We were right next to a factory of some kind where there was nobody on weekends. The roof was kind of a hot place. We put benches up there. In the summer, we would sometimes cook hamburgers up there. One anniversary, we had a blacksmith from Ohio, Larry Schwartzenberger, who had a forge for handcuffs and things like that. He came up and set up a forge and anvil and we had a branding.

Jack Fritscher: A lot of noise from the forging and yelling?

Wally Wallace: We always had to worry about that. Some of the S&M stuff, slings, and so on. Sure, there was some screaming. We had to use gags sometimes. There wasn’t a lot of S&M going on; everybody wasn’t into that. But we did have bondage equipment developed over a period of time. I would get ideas from going to Inferno [an annual S&M outdoor leather bike run] in Chicago, A-frames and crosses, that sort of thing. We had them available for guys.

Jack Fritscher: What was the most outrageous S&M scene you saw in the Mineshaft?

Wally Wallace: I don’t know if you would call it outrageous, but we had a back bar. You couldn’t depend on the customers — once they disappeared into the backroom — to come out again to the front bar. Of course, the owners of the business were mainly interested in selling beer. So on weekends we added this little back bar to sell beer. Then we eventually added a bar downstairs, which was also very popular on weekends.

Anyway, I had become very good friends with Leather Rick.

[Leather Rick shot and starred in outrageously extreme S&M videos at the Mineshaft featuring guys from the biker club called “Skulls of Akron.” In their feature, Fisting Ballet, the action is typical rough and real Mineshaft play. The videos also incidentally document some of the interior set, the gay space, of the Mineshaft rooms.]

I had met Rick at the first Inferno weekend I attended, and we remained good friends. It was on a New Year’s Eve, I think, he nailed somebody’s cock down on the back bar. The guy was sitting up there on the bar waiting to be nailed. Somebody asked if the nails were sterile. I happened to be there. “Of course, they are,” I said. I had no idea if they were or not. This was before AIDS. I didn’t know a lot about S&M. I knew about leather. I’ve never been a big reader of gay porno, although I like Drummer. You were the first person to write about the Mineshaft.

Jack Fritscher: Thanks for remembering. I wrote about you twice. [Drummer 19, Christmas 1977; Drummer 20. January 1978]

Wally Wallace: The only porno films I really liked were the Joe Gage films, Kansas City Trucking Company, etc., because there was a story built into them, showing environment and context along with actual sex. I did read Mr. Benson by John Preston, a lot of which revolved around the Mineshaft, but I don’t read a lot of fiction.

TIMECODE: 1:14:45

Jack Fritscher: Did you know John Preston?

Wally Wallace: Yes. I had a run-in with him once. The very first year there was a New York “leather contest.” It was hosted by Interchange. John Preston was sent by the owner of Drummer to photograph the event. This was the second year of the contest which was held in the Paradise Garage. My job was as Special Events committee, involving security and photographers. Because there were already two other people covering the event for Drummer, we had to tell John Preston not to take pictures and he got very upset. He wanted to get in free and we said, “This is a benefit. There are no comps.” He argued about it, but eventually paid. He definitely had an arrogant streak that just rubbed me wrong.

Jack Fritscher: Preston was problematic inside Drummer as well [during and after I was editor-in-chief]. After he was fired by The Advocate, he came hat in hand to us to work freelance, but he didn’t stay long.

Wally Wallace: Rules get set up and sometimes get followed to extremes. For instance, at Inferno in Chicago, there are very strict rules about photography because there are people there who don’t want to be exposed, do not want anybody taking their pictures. In the Mineshaft for the first four years, we would not allow photos. I remember one time we let a guy, George Dudley, come in and shoot some pictures, including our flag and flagpole.

[George Dudley (1949-1993, AIDS) was a photographer and artist who founded and owned the nostalgic American Postcard Company and also served as the first director of New York City’s Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art.]

In those days, because of all the Bicentennial celebrations, most leather bars, including the Mineshaft, had an American flag. Not the case today. Our flag was cloth with Christmas lights behind it. Later I bought a hand-crocheted flag from a friend. We would use that flag when we did our Mineshaft Man contest.

TIMECODE: 1:20:58

Jack Fritscher: Robert Mapplethorpe shot pictures of that.

Wally Wallace: Yes, I have one of his shots right here.

Jack Fritscher: That’s David O’Brien, Mr. Mineshaft. I have a copy Robert gave me.

Wally Wallace: Bob only shot one of our Mineshaft Man contests, and David O’Brien was the winner that year; so it was about 1979-1980. Somebody thought Bob could take pictures of the event. But that wasn’t his thing. But he took some posed pictures of David. I don’t remember if he ever shot anything else there.

By the way, the Mineshaft Man contest was not to pick “Mr. Leather,” or “Mr. Muscle,” or even “Mr. Mineshaft,” but to pick a guy who epitomized what the Mineshaft was all about: “The Mineshaft Man.” The judges were people who usually went there, or who were in gay businesses. One guy who did look “like a recruiting poster” was Mark Pongie [approximate spelling]. He was partially deaf, and read lips: a sweet, nice guy. I was really proud to see him win.

Rex did three posters: for the first contest, of a miner with arms raised hoisting a big Mineshaft sign; for the second one, of the guy with the pick and hard hat; but the third one never turned out the way it was supposed to. It was of a guy with a jackhammer in the street. Something was lacking. Rex himself was wonderful. Not easy to get to know, but he’s a wonderful human being.

Some of the male pornographers, you know, are like Michelangelo. There’s our Tom of Finland and A. Jay [Drummer art director Al Shapiro]. A. Jay’s posters from the Caldron [This is the correct spelling.] were wonderful. I hope someone saved them. I got to know Jim [Gilman] and Al [Shapiro] at the Boot Camp [a pissoir-bar on Bryant Street in San Francisco]. When Jim and Al were putting together the Caldron [with Hal Slate who managed the Castro Theater in San Francisco], they came to New York City for a long weekend to observe things in the Mineshaft.

What did they observe? Did they observe the backroom activities, etc.? No, they looked at our coat-check system and adopted that. They were interested in exploring how the Mineshaft systems worked. And I think it paid off for them like it did for us. We didn’t lose checked clothing because we had a good system that guys trusted and we lost very few coats. The ones we did lose, we paid for. The Mineshaft was pretty safe that way. That’s important in an operation.

Jack Fritscher: At the time you mention, 1979-1980, Robert Mapplethorpe was just beginning to become a sort of a celebrity in his own right.

Wally Wallace: Yes, right, but I knew him as a person. I liked Bob. We weren’t close friends, but we’d talk and compare notes. I remember one time [hesitates], well, he liked black men. He had heard of a place in Times Square called Blues, which was a black gay bar. One of the few places that was openly promoted as a black gay bar. And Bob was afraid to go there. I don’t why, but he was. So I went up there with him one time. He was like a kid so eager to go, but so afraid to go alone that you might have thought it was in the depths of Harlem. The night we were there, there weren’t many hot men, but only a couple of drag queens with their white boyfriends. It was not what he imagined. I know he went back there a few times. I know he went to Keller’s a lot. That has now become a black bar. It was one of the original New York leather bars. It’s still there; one of the longest-running gay bars. Never talked much to Bob about his work. You didn’t talk about work at the Mineshaft. You talk about what’s going on in town, neighborly talk.

Jack Fritscher: Let’s talk about some other celebrities who came to the Mineshaft. I heard Mick Jagger was once turned away.

Wally Wallace: Yes, Mick Jagger was turned away because he was with a girl [Jerry Hall, the Texas model who became his wife for a Warholian fifteen minutes]. He probably would have been let in if he was alone. I know that because I was there that night. I was there a lot, but not always, and I can’t vouch for some things that are reported to have happened. I may have been home sleeping. I certainly was not there all the way from Friday night to Monday morning.

Jack Fritscher: What was it like to scrub the place up after a long weekend?

Wally Wallace: It was pretty bad. We would have a problem in the tub room if the guys used too much bleach because the vapors would come upstairs. I think the Mineshaft was a lot cleaner than people perceived it to be. We kept it pretty clean. It was an old concrete building. We eventually had to nail up plywood over the plaster wallboard because people having rough sex and shoving up against the plaster board would put holes in it and the inspectors were always having to tell us to replace it. One of the biggest problems we had was the scatzies [scatophiliacs] what with their drugs and everything. We tried to discourage that kind of dirty sex, but people would do scatzie. We always had floor men on duty to clean up.

The Mineshaft employees had a certain camaraderie. On Saturday night, I would have as many as fifteen guys on duty. We had three bars, with three or four in the coat check, and doormen. We had one doorman and one assistant manager to make the money pulls from the various in-house bars. We didn’t have cash registers and couldn’t keep money in the house due to the [Mafia] owner’s policy. So we were constantly collecting money from the various bars. Then we had three floor men. Then, when the can-recycling thing came in, that was a whole new operation.

TIMECODE: 1:40:59

Jack Fritscher: Tell me about the time the Skulls of Akron biker club came to make a video in 1981 or so. Was that the first video shot in the Mineshaft?

Wally Wallace: No, the first video happened like this. One of the guys who worked at the Mineshaft had a friend who made movies. He came from France and wanted to shoot a porn film at the Mineshaft. Supposedly, this would only be seen in Europe and not in America. We got a little money, but it was a strange film. It was a French version of what they thought the Mineshaft was. They tied one guy up and put Christmas lights around him so he looked like a Christmas tree. I remember Camille O’Grady was in it.

Jack Fritscher: I know the movie. It was New York City Inferno [1978, directed by Jacques Scandelari].

Wally Wallace: When you’re recording music for a movie, you have to pay attention to the sound balance. The music on the video had a horrible echo and did nothing for Camille’s career. She thought it would. She did sing at the Mineshaft a couple of times for benefits. We did a lot of benefits. We would also hold casino nights during the week, no sex.

[The first Mineshaft flyer for Christmas 1976 advertised: “Upcoming special events include the opening of our new tunnel playroom, a ‘Criscomas Party,’ and a repeat performance by Camille O’Grady.” Wally also invited Camille to sing her piss song “Toilet Kiss” at the Mineshaft 1978 anniversary party.]

But getting back to the French movie, the plot was that a Frenchman came to the U.S. to find his lover who has been made a slave. And his way to find his lover was to take the seven days of letters he had received and follow them from place to place, which was totally ridiculous, of course. But there were a lot of hot things in the movie. One of the hottest was when he arrived in the States, he meets a taxi driver who takes him to the meat market where he is seen having sex in the freezer with all these sides of beef hanging around.

And then he’s seen in the Mineshaft, but it didn’t look like the Mineshaft. They only used a little piece.

[Scandelari featured Camille and her band on a raw wood stage which was a landing half-way up the interior wood stairs in the middle of the Mineshaft that Wally had found under the go-go boys’ box.]

The only time the Mineshaft looked like the Mineshaft in a video was one made later by the Gay Men’s Health Crisis. It was in three segments. The first segment was a couple getting together for a date while they talk a lot about having safe sex, put on rubbers, etc. The last segment was about something out on Fire Island. The middle segment was filmed at the Mineshaft and was about S&M, but there was no narrative to explain what parts of S&M were safe and which parts weren’t.

Jack Fritscher: What is the most outlandish gear you ever saw worn in the Mineshaft?

Wally Wallace: Gear?

Jack Fritscher: Well, costumes, leather, rubber, the hottest thing?

Wally Wallace: The Mineshaft didn’t make that big a thing out of Halloween. We were on the north end of the Village, twelve to fourteen blocks away from the center around Christopher Street where everybody went on Halloween. But we did some things. I think the hottest costume gear was, maybe, [sounds like] Bo Shear, one of the regulars — he was Dracula cuming in his coffin. He had a big dick and an air pump, and some fluid would come out every once in a while. As far as day-to-day gear, I can’t think of anything other than leather. We had masks sometime, usually made out of metal rather than leather.

Jack Fritscher: Tell me more about how you managed the action to keep the party under control.

Wally Wallace: So, to get into the Mineshaft you had to walk up some stairs and at the top of the stairs was the doorman. Now he had to determine whether the guy coming up the stairs — if he was too drunk or too stoned he couldn’t get in. The same ones would show up again and again.

We did have a few problems with pickpockets. These guys were professionals and would sometimes work in teams. They would get into the Mineshaft, and one of the guys on the team would get naked. Now we would do everything possible to get guys to check their wallets. We had signs. We made announcements. We did everything possible because we never lost that sort of stuff when it was safe in our coat check. Through all the years we had never had anybody lose anything in terms of money he’d checked. We lost a few jackets by transferral. Like I said, these guys would work in teams in the tub room, which got pretty crowded. The naked one would pass the wallet to his cohort. It’s hard to accuse a naked man of hiding a wallet. When we caught these guys what we did was throw them out on the street without their clothes. I know of at least three occasions where somebody was thrown out totally nude, sometimes in winter. This kind of thing made me mad. We sometimes wondered what happened to them.

Jack Fritscher: Just like an Old West saloon, throw them out through the swinging doors. What is the sexiest thing you ever saw there?

Wally Wallace: Saw? OK, but I won’t tell you about anything I participated in. Well, there were some men there — whatever they were engaged in was sexy. We had some very hot men come in to play. Hot. It’s not always body. It’s a sensuality that some people have. We had some events — one was called the “School for Lower Education.” One was called the “Black Mask” where everybody wore black masks. These events were once a year, special. We had some demonstrations mentoring S&M. We let the GMSMA do a demonstration for a part of the door, that sort of thing. They would put on some wonderful things. A lot of the bondage stuff.

Another thing that went off very well the first few times we did it — and then it died because you couldn’t get contestants — was a body painting contest. We would supply the paint and one guy would paint another.

[In the cross pollination of Drummer and the Mineshaft, Drummer featured Val Martin, star of Born to Raise Hell, with his body painted by Chicago tattoo artist Cliff Raven on the cover of issue 8, published September 1976, one month before the Mineshaft opened.]

I remember Camille was involved in one painting contest. She was a talented artist. Greg Maskwa was one of the artists doing the body painting. He did some nice things [kinky drawings of leathermen and women]. One of the most interesting things was a lot like the “Emperor’s New Clothes.” This one guy was painting this other naked guy forever with this solution. It was invisible. I didn’t know what it was. It didn’t look like anything, but it was a sort of clear plastic that peeled off. The guy was totally encased in it. Cock, balls, everything. It was like a third skin. You think of leather being a second skin. This was an invisible skin. I’ve never seen that again.

Jack Fritscher: Is there anything special you’d like to say about the Mineshaft? What do you think the Mineshaft esthetic did to help create the 1970s as we know them, that high golden age? Maybe you could say something about the movie Cruising.

END VIDEOTAPE #1

START VIDEOTAPE #2

TIMECODE: 01.00

Wally Wallace: Well, you know the book was based on gay murders [in the 1960s], but it had nothing to do with our leather scene. [The book Cruising was a fact-based novel written by New York Times reporter Gerald Walker in 1970, six years before the Mineshaft existed.] I don’t know how the director [William Friedkin, director of The Boys in the Band and The Exorcist] found out about the Mineshaft. I heard he got in at some point or other before filming, maybe six months before. He recruited a lot of guys in our leather scene to be in the film. Most were not actors. He held auditions for quite some time and got a lot of legitimate leather people involved in it. I was approached by one of his crew who wanted to come into the Mineshaft to shoot stills for their storyboard. So I let him come in just to hear his pitch, but he said the ceilings were not high enough for the lights and cameras necessary to shoot a movie. So I met him — before I met Friedkin, but finally I would not agree to them coming in. I could not see any point, any advantage for us. We had that rule about photographs. We only let friends like Mapplethorpe shoot pictures.

We didn’t do commercial things. The Mineshaft never advertised, except for inserts in benefit programs. Whatever money I made hosting a benefit went back to the benefit. The mob owners were not generous, but I sure was. We didn’t advertise because we were supposed to be a private club and the members were supposed to introduce us to new members. Of course, word of mouth was our best source. We got the people we wanted that way.

So I refused Friedkin, and then a couple of my staff got involved in the movie. Others on the staff didn’t want anything to do with it. Their main objection to the film was the portrayal of gays as murderers. There was a boycott protesting the movie led primarily by a guy named Joe Smenyak [who that same summer of 1979 helped organize the first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, and later appeared in the 1983 production of Doric Wilson’s Street Theater which had premiered in 1982 at Theater Rhinoceros in San Francisco]. So it was never filmed at the Mineshaft, although to this day a lot of people think it was.

The bar scenes were shot at a place now known as the Cell Block, but at that time, it was another after-hours place — before that space became the Hellfire Club — in the basement of the Little Triangle Building at 14th Street and Ninth Avenue. I can’t remember the name at that time. It is a unique space. It is underneath the street, not under the building. Historically, there was a canal from the river up to that building. The Little Triangle Building at the time of the Civil War was a Union Army barracks. After the war it became a hotel. I think Herman Melville lived there when he was writing Typee. Later I ended up in a loft space on the top floor, but that is another story.

Anyway, let me backtrack to when they still wanted to film Cruising at the Mineshaft. They kept trying to get permission to shoot still shots [for their set designer], but I refused. And later, when we had our first raid on the Mineshaft, it had to do with liquor violations and a few other things. Actually, and here’s the point. It turned out that the raid had been staged [arranged] by some guys in the movie company, because their security force were ex-New York City policemen. One was Sonny Grosso, who is now a big author and producer of some of the big TV crime series. [Grosso played the part of Detective Blasio in Cruising.] These were ex-cops who had been involved with the famous “French Connection” crime case, who had since left the force and were now doing movie work. [Friedkin had directed the cop drama The French Connection in 1971 after he had directed The Boys in the Band in 1970.] So these guys arranged a police raid on the Mineshaft on the basis of liquor violations [when all they wanted was photos of the interior.] This all came out later in a grand jury investigation. Everybody working at the Mineshaft was taken downtown in a paddy wagon, including me. I wasn’t even there when the raid took place; but when I went there to find out what was going on, I was put in cuffs, totally illegally and taken down to the station house.

While we were downtown, a crew from the movie company went into the Mineshaft and photographed everything.

I was arrested illegally, but all charges were eventually dropped after going to court.

I think Friedkin, or maybe his set designer, had this obsession to re-create both the interior and exterior. After I refused, in order to create the exterior, he hired the meat company which is right next door to the Mineshaft where he filmed all his entrances and exits to the bar in the bar scenes in the film. In the movie, people go downstairs after entering, whereas in the Mineshaft, of course, you had to go upstairs. Otherwise it looks exactly the same. We didn’t have a sign that said “Mineshaft.” We just had little arrows that said “Private Club,” and that was what he re-produced.

Jack Fritscher: It’s interesting that sometime later when you first began to have a movie night at the Mineshaft, the first 16mm film you projected on the screen in the main bar was Cruising.

Wally Wallace: It was interesting to see the faces of so many Mineshaft regulars on screen.

TIMECODE: 11:52

Jack Fritscher: What do you think has been the Mineshaft’s contribution overall to the way we are, the way we were?

Wally Wallace: I think we allowed — we gave guys — a sense of freedom, to sort of sow their oats.

Jack Fritscher: Sow their oats and spill their seed.

Wally Wallace: Right. Sex is many things, never a cut-and-dried subject. The form of sexual activity that we had at the Mineshaft is, in one sense, like people going to the gym to work out. It is an exercise, recreation. But it also spiritual, like going to church. Of course, it was hedonistic. You can’t deny that. But it was a form of recreation for a lot of people.

Without going into names, we had people who were famous in their professions. We had the cream of the crop. We had a lot of clergymen, including Catholic clergy, theatrical people, stage managers, directors. A lot of gay marriages happened out of the Mineshaft. I know several couples are still together who met at the Mineshaft. Partnerships, collaborations. The front bar was a great place for talking. People at other bars would stand there all night in those bars posing or cruising. At the Mineshaft, people could relax.

The Mineshaft was a neighborhood bar, but it included all of Manhattan. After all, Manhattan is a relatively small island and most of the people live south of 80th Street. So nobody was that far from the Mineshaft in terms of where people actually lived. It was a form of recreation. You needed a place to go after working at a high-pressure job all week and we provided the place to relax. We had dress codes, but they were for a reason. We dealt with a particular clientele, but we didn’t see it only as a business.

Other people have tried to imitate the Mineshaft with only money in mind, and haven’t succeeded. You have to have other concerns. We, including my staff, gave a lot back to the community. One thing I am personally proud of is that we happened at a time when a lot of things were being created in the gay community, like the Gay Men’s Chorus, gay bankers, gay businessmen. We were there at the start of AIDS. We raised a lot of money along with other gay bars like the Badlands for serious and fun things like “Butts for Tuxes” for guys in the Gay Men’s Chorus to wear their first tux to their concert in Carnegie Hall. Gay theater.

The Mineshaft opened seven years after the Stonewall riot. Stonewall was political, but it took a good ten years afterwards to create cultural organizations. Some of the discos were happening at that time.

[The original Studio 54 opened five months after the Mineshaft opened, and ran from 1977-1980 when it was shut down because owners Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager, defended by Donald Trump’s then attorney Roy Cohn, were convicted of tax evasion. Schrager was fully and unconditionally pardoned by President Obama in 2017. In 1981, Robert Mapplethorpe shot a revealing portrait of the gay Roy Cohn making his evil face a mask floating disembodied in a field of black. In the 1950s, Cohn had conspired with the severely anti-gay demagogue Senator Joseph McCarthy and had prosecuted Jules and Ethel Rosenberg who were executed in the electric chair at Sing Sing. In 1986, Cohn was disbarred for forcing a dying client to sign his fortune over to him — five weeks before Cohn died of AIDS.]

The gay churches too. My aunt and uncle, a childless couple, went to a church in Washington Heights, and they couldn’t understand why their minister would go from Washington Heights down to the Village to “work with those homosexuals.” Little did they know that only two weeks before, I had hosted the Everard fire benefit with that very minister.

TIMECODE: 21:43

Jack Fritscher: You’re so generous to share your story. You must be exhausted — unless you want to name some names, for the record.

Wally Wallace: Well, I know Rock Hudson was there once. He came with [unintelligible] Wilson [not Henry Willson, the agent who discovered him]. Al Pacino definitely was there — but not as a gay man — for his role. I think he was duped into that role. I heard he didn’t really want to do it. As far as I know, he’s heterosexual. That was a weird movie, Cruising. It was being filmed at the Hellfire. There were protestors day and night. Cops guarding the set. And the company [he alleged] was passing out dope to the gay extras. Pete [unintelligible] was in the film for a couple of days before peer pressure got to him. He can vouch that everybody was stoned. The guy that danced with Al Pacino, Bruce [Levine], was a friend of mine. You would think all that publicity would get them a great movie, but it didn’t work out. Not just because of the gay protest, but because it wasn’t a very good movie.

Jack Fritscher: That protest was probably the highest public profile the Mineshaft had.

Wally Wallace: Well, sure, except when we were closed.

Jack Fritscher: Tell me about how you were closed.

Wally Wallace: Well, it was so unofficial. The cops came down during the day. We had been closed the night before. They sent in inspectors. This is really important. This was a task force. This [NYPD] task force was advised that there was a gay, kind of self-policing group, working internally within the city government and state too, I guess, to self-police sexual activity in places where sex was taking place.

One of the people on this board was a woman who may be gay, Ginny Apuzzo, but what does she know about our lifestyle?

[Wally meant the “leather lifestyle.” In truth, in her long career of service, Virginia “Ginny” Apuzzo, a former Catholic nun, was executive director of the National LGBTQ Task Force and served as executive deputy of the New York State Consumer Protection Board and as the vice chair of the New York State AIDS Advisory Council, and was the most senior openly gay person in the Clinton administration. On March 24, 2020, under gay archivist JD Doyle’s Facebook photo of her, she wrote in response to a comment I posted about her and the Mineshaft: “It’s curious…nearly half a life of advocacy and recalled for closing the Mineshaft.” Sometimes history writes us. I reassured her that neither Wally nor I meant to be reductive: “In your valued career, you did a good thing for the community and public health in helping close the Mineshaft. Thank you.”]

A couple people from the Mineshaft met with this board, and we did everything they asked, like condoms and passing out literature.

They sent in employees from the Consumer Affairs Office. They did not send in police to make reports. In the reports — and there were something like twelve different reports — not one mentions any sort of anal penetration of cock to ass. Not one talks about any oral penetration, cock to mouth. What they talk about is deep kissing, moans being heard in the backrooms, not even seen. In other words, it was all light S&M acts in these reports. Now this is the Mineshaft. I can’t speak about the baths and other places. I never saw them. But the Mineshaft report was posted with great publicity on the door, with TV coverage. The precinct captain was there, even Mayor Koch made an appearance. I was watching on TV with the owners. As I say, nothing, not one real sexual act was mentioned because it was really about taxes, because the owners had this tax situation.

[In the perfect storm of taxes and AIDS, Wally told me off camera: “By 1984, the year before we closed, profits dropped so sharply that the [straight] owners called me in, and my staff, one by one, saying we were skimming the cash register. I told them AIDS was killing their customers.”]

TIMECODE: 29:56

Jack Fritscher: So why do you think this self-policing gay group had an agenda to shut down the Mineshaft? What was their motivation?

Wally Wallace: The same as always. The gays are always embarrassed by the leather community. They don’t think we represent them well. They are embarrassed that we exist in the same world. But shouldn’t we be embarrassed by men who pose as women? To get personal for a minute. A lot of people think I am anti-women, anti-drag queen. As a human being, I am not. We each explore our own territory. If they don’t infringe on my territory, I don’t infringe on theirs. I think some of the leather women are wonderful, but I don’t want to have sex with them or go to bed with them. I’m a gay man. I like men.

Jack Fritscher: Erotic psychology is rarely politically correct.

Wally Wallace: When it comes to talking S&M techniques with women, I’m all for it; but I think we can have our separate playrooms. At this moment, I’m glad to see all of us seem to be getting together. But in the past, it has been the women who have been as alienating as the men. And, of course, these leather women are looked down upon in their lesbian community in the same way leathermen are in the gay community. The S&M women’s groups are outcasts in the lesbian community. I’m glad to see there is a better rapport now between the two groups.

There does seem to be a barrier now between the older leather guys and the young punk gay leathermen, but we shouldn’t be apart just because we come in by different routes. We all have to live in the greater world.

Jack Fritscher: Thank you very much.

Wally Wallace: I want to give you some of this stuff [eighty photos for my use with this interview and articles based on this interview.]

Jack Fritscher: This is March 28, 1990.

Wally Wallace: Oh! At one of our Mineshaft Man contests, one of our judges tells me and another judge that he thinks he recognizes one of the contestants [Michael Garrison] as a man who seven years before had murdered the lover [Tom Strogen] of a mutual friend [Rob Kilgallen]. He tells us this during an intermission. So the two of us go to our mutual friend sitting out in the crowd and he confirms this. [The contestant] had murdered the lover, had gone to trial, and three years later he was out of jail, and now, a few years later, was in the Mineshaft Man contest.

Jack Fritscher: Cruising, anyone?