NON-FICTION BOOK

by Jack Fritscher

How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

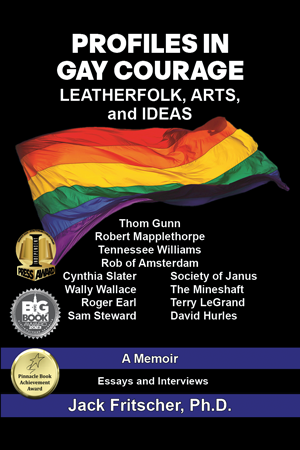

PROFILES IN GAY COURAGE

Leatherfolk, Arts, and Ideas

Volume 1

by Jack Fritscher, PhD

Also available in PDF and Flipbook

ROGER EARL

1939-

Born to Raise Hell: Two Filmmakers in Conversation

April 22, 1997

Curating the BDSM Film History

of Roger Earl and Terry LeGrand

Popularized in Drummer Magazine

Roger Earl: [Answering phone] Hello from Los Angeles.

Jack Fritscher: Hello from San Francisco.

Roger Earl: Hi, Jack. Right on time. I love that.

Jack Fritscher: Are you ready for your closeup?

Roger Earl: Absolutely.

Jack Fritscher: How are you doing?

Roger Earl: I’m doing fine.

Jack Fritscher: Good. Is it alright with you if I record this?

Roger Earl: Fine.

Jack Fritscher: OK, we’re recording. Let’s start in the middle of things the way Greek dramas start. Let’s go back to that romantic night in June 1989, when Terry [LeGrand] kissed me on the boat in Amsterdam, on the canal. Remember that? We all had a laugh.

Roger Earl: Terry probably did it. Do I remember it? No.

Jack Fritscher: We have a photo Mark [Hemry] shot. He and I had just flown in from California hauling your huge trunk full of lights and cameras that at a couple hundred pounds was not so much carry-on luggage as it was freight. We had just landed at Schiphol [Airport] to shoot on location for you.

Roger Earl: Probably that’s why Terry kissed you. We were both so happy to see you.

Jack Fritscher: [Laughs] That first night, you and Terry took us on a dinner-boat tour on the canals of Amsterdam. Two couples. You: a pair of friends. We: lovers. Very romantic with all the lights on the bridges and buildings. It was sweet. Mark and I always remember your gesture very fondly.

Roger Earl: Terry and I had been there in 1988 shooting films.

Jack Fritscher: Just to be clear: that was for your Dungeons of Europe trilogy which came out [in 1988] just before your Bound for Europe series of six videos we shot for you [in 1989].

Roger Earl: Exactly. Dungeons was filmed in England, Holland, and West Germany.

Jack Fritscher: And we shot Bound in Holland, Germany, and, more specifically, West Berlin, which was, as it turned out historically, the last summer that West Berlin existed. Did you know that the Christmas after the Berlin Wall fell in November Terry sent us a small chunk of souvenir cement from the wall?

Roger Earl: Terry is a good and thoughtful producer.

Jack Fritscher: And an industrious entrepreneur! Remember how he provided the crew with new leather vests identifying our names embroidered in red on the front and “Marathon Films” on the back. Mark and I were happy he admired the fetish and S&M reality features we shot for our Palm Drive Video studio enough to trust us to shoot in our style for your Marathon Studio. Even though I was with you on location, I’m curious. I remember you told me that Born to Raise Hell was your calling card because it was so famous in Europe that it opened doors and dungeons. Men were eager to work with you. How did you feel as an American director shooting twice in Europe with European leathermen personally and authentically dedicated to S&M?

Roger Earl: Actually, I consider the 1989 Bound shoot with you as a continuation of our first experience of shooting in Europe.

Jack Fritscher: Your first three European features in Dungeons were Pictures from the Black Dance, Moths to a Flame, and Men with No Name.

Roger Earl: Yes. Three films. So the six-video series you shot for me was sort of a continuation of that…

Jack Fritscher: There’s definitely a narrative thread connecting your last nine films [Dungeons and Bound]. I can see that in the fact that Terry contracted Mark and me to shoot three features on two cameras out of which footage you actually cut six interconnected features for Bound.

[Bound for Europe: The Six-Feature Video Series, Directed by Roger Earl and Produced by Terry LeGrand of Marathon Films, Cinematography by Jack Fritscher and Mark Hemry of Palm Drive Video; Production Date: June-July 1989, Released Serially: 1990-1994

1. Argos: The Sessions, shot in Amsterdam

2. Fit to Be Tied, shot in Dusseldorf

3. Marks of Pleasure, shot in Hamburg

4. The Knast, shot in West Berlin

5. The Berlin Connection, shot in West Berlin

6. Loose Ends of the Rope, shot variously in Amsterdam, Hamburg, Dusseldorf, and West Berlin]

Roger Earl: …And [in that connective narrative] we were using Christian Dreesen again, and shooting in locations we had not gone to earlier.

Jack Fritscher: Ah. Making a connection of shooting Christian in the Connection Club bar in West Berlin for The Berlin Connection. Christian was sex-bomb star. When Terry brought him into the hotel lounge to introduce him to us crew, the entire room fell silent. [Dreesen later became both Mr. Germany Drummer and Mr. Europe Drummer: Drummer 147 cover, March 1991]. How much of Dungeons was shot in England?

Roger Earl: A lot in England. Most of the rest in Amsterdam.

[As the founding San Francisco editor-in-chief of Drummer, may I recommend journalist Kevin Wolff’s interview, “Roger Earl: S&M Auteur,” in Drummer 126 (March 1989) in which Earl explained that he decided to shoot Dungeons in Europe because no American director “had done this, and I’d read so much about Europe in Drummer, and in some of the magazines I’d gotten through Larry Townsend from Europe. It looked like a pretty good scene over there…. It all developed from starting to talk to Bryan Derbyshire, of HIM Magazine. Larry Townsend had put us in touch with most of these people…credited at the end….We didn’t know what we were getting into, what kind of locations we’d have, or if we’d even get people. We went over there really on speculation.”]

Jack Fritscher: So our Bound crew then went to five cities in Germany and met all those wonderful German leathermen.

Roger Earl: The Bound series got us to Hamburg and…

Jack Fritscher: Dusseldorf and Cologne and Frankfurt…

Roger Earl: And West Berlin. But I’m thinking about that wonderful club [Terry scouted] in Hamburg, the famous German S&M club, where nobody had ever been allowed to shoot before, and it turned out wonderfully.

Jack Fritscher: That was the dominatrix’s place?

Roger Earl: No, no. There was an upstairs and a downstairs, and they had the cages and everything. It was like a clubhouse. The one you’re thinking of is in Dusseldorf.

Jack Fritscher: As a cameraman, my recall of the locations is limited because I mainly saw them through my black-and-white viewfinder. In my memory, what was in the camera is more real and lasting than the reality that was real and evaporated. As the director, you processed the entire mise en scene. But, yeah. I do remember the Hamburg club you’re talking about because that’s where that hot “Beast of Hamburg” appeared in the door. That breed of German leathermen was fierce and wonderful.

Roger Earl: What a turn-on they were. They were very serious people who knew what they were doing. It was like watching a ballet to see them play.

Jack Fritscher: When I look at our footage that you’ve edited together, and it’s a good job of editing, by the way, I really like what you’ve done. That shoot that Mark and I did was your first two-camera shoot, wasn’t it?

Roger Earl: Yes, it was.

Jack Fritscher: And that requires a whole new set of conceptual editing skills. A novice can sit down and edit the footage from one camera, start to finish; but to interpret and cut footage from two cameras is really…

Roger Earl: It becomes a little more difficult, but I like it mainly because [with footage from two rolling cameras giving twice the dailies] I feel that I don’t really miss any on-set action while one or the other camera is moving to another angle. When you’re shooting an S&M sort of [reality] thing, it’s not like you can say, hey, cut, wait, let’s go back and start at the beginning.

Jack Fritscher: Going back to the beginning, to your debut film Born to Raise Hell. I remember going with a group of leathermen to its San Francisco premiere at the Powell Street Theater, just by the cable car turnaround at Market Street. Standing room only. The struggling Powell was just then turning into a porn theater. Terry must have four-walled it, because the premiere of Born started at 10 AM so the manager could start screening his scheduled triple-X double feature at noon. Was it 1975?

Roger Earl Marathon Filmography in Drummer

Drummer 3 (August 1975) Cover and photo feature, Born to Raise Hell

Drummer 78 (September 1984) Back cover and photo feature, pages 10-17, Chain Reactions

Drummer 114 (March 1988) Back cover and photo feature, pages 8-15, Pictures from the Black Dance

Drummer 125 (February 1989) Cover: Christian Dreesen, Like Moths to a Flame

Drummer 126 (March 1989) “Roger Earl: S&M Auteur,” an interview of Roger Earl by Kevin Wolff with photo spread, pages 42-45

Drummer 133 (September 1989) Photo feature, Men with No Name

Drummer 144 (November 1990) Cover, Christian Dreesen as “Mr. Europe Drummer”

Drummer 147 (March 1991) Cover, Christian Dreesen as both “Mr. Europe Drummer” and Mr. Germany Drummer,” with Dungeons of Europe guided-tour feature

Drummer (Special Publication as separate magazine) Born to Raise Hell (still photography), 64 pages, 1975

Drummer (Special Publication as separate magazine) Chain Reactions (still photography), 64 pages, 1985

Mach 14 (February 1988) Interior photo spread, Pictures from the Black Dance, pages 34-41

Mach 15 (May 1988) Interior photo feature, Like Moths to a Flame, pages 30-35 (misnamed on the cover as Pictures from the Black Dance)

Mach 17 (March 1989) Like Moths to a Flame, pages 30-35

Mach 19 (January 1990) Men with No Name, pages 46-51

Mach 20 (April 1990) Cover and interior photo spread, The Argos Session (cover and stills shot by Jack Fritscher)

Roger Earl: Close to it.

Jack Fritscher: I often see the Born release date misquoted as “late 1970s” when it was actually shot in mid-1974, and released in 1975.

Roger Earl: I believe it was.

Jack Fritscher: In a timeline, I remember that Born was immediately showcased on the cover and inside the third issue of Drummer magazine in August 1975, as well as in the special Drummer spin-off publication of your stills titled Born to Raise Hell. You were good for Drummer business and Drummer was good for yours. I counted nearly a dozen Drummer covers and interior spreads dedicated to your work. Plus covers and coverage in five issues of the Drummer sibling magazine, Mach, including the cover of Mach 20 which, you remember, I shot the first night in the Argos bar, for The Argos Sessions, when I was shooting the stills before you hired David Pearce to do that because, as you may recall, I told you it was impossible for me to shoot both the Hi-8 video and the 35mm stills of scenes that were one-take chances. Your relationship to Drummer was symbiosis. Perfect marketing. Your photos were a hit with readers who turned into viewers of your films.

[During twenty-four years, the 214 issues of Drummer, with a 42,000 press run per issue in the l970s, were read, quite literally, by millions worldwide.]

Roger Earl: You know Drummer better than I do.

Jack Fritscher: Just as Drummer depended on you to fill our hungry monthly pages, the gay films of the 1970s depended on gay magazines to get publicity and esthetic respect. When I see your name in magazine ads for your very successful Marathon film company, and people writing reviews, they always call you a filmmaker. And you are a filmmaker, but like all us directors, you evolved into a video maker in the early 1980s. Do you remember coming out into the hallway of our hotel in Amsterdam? That wonderful hotel, the Victoria, directly facing Centraal Railway Station? Terry had a little device in his hand, and you and he told us it was the latest high-tech thing: a camera that did not use film.

Roger Earl: Absolutely. I’m a filmmaker who graduated to video. And to digital. Way back when, I edited Born to Raise Hell on my dining room table, cut from original 16mm film.

Jack Fritscher: On a Movieola?

Roger Earl: No, not on a Movieola. On one of those little Moviescopes.

Jack Fritscher: How long did it take you to edit Born?

Roger Earl: Oh God, three to four weeks. Mainly because I had hired someone to do the actual cutting while I was making all the decisions. We were cutting the original color footage because I couldn’t afford to make a work print. Believe me: I didn’t want to screw up the original. His name was… He was a lover of one of the Christy twins. He did a couple of films as a director/photographer.

Jack Fritscher: Yes, the twins. Did you know the Christy twins?

Roger Earl: One of them used to come over and sit in the patio while we did our editing. [On Born, Tim Christy was assistant sound editor and sound recordist.]

Jack Fritscher: Tim and Chris Christy and their gay porn films! Twincest as taboo in that first decade after Stonewall. [I shot my Palm Drive feature Twincest with the Blake Twins in 1992.] Were they from the South?

Roger Earl: I think so, from the San Diego area originally. Vince. That’s it. Vince was the first name of the editor on Born to Raise Hell. I’ll think of his last name before this is over. Vince Trainer. That was his name. He did the physical cut.

Jack Fritscher: How many prints did you make for theatrical showing?

Roger Earl: I don’t really know. Terry did that and I think he had three or four made.

Jack Fritscher: How did you meet Terry?

Roger Earl: I was working at NBC, had gotten a job there, in Burbank. I had gone to a party in the Hollywood Hills and met this older gentleman named George who was very hunky and I ended up in the basement with him, whipping his ass on the staircase. He had got me my job at NBC. Later on, he came to me and said, “I’ve got some friends who want to make a very heavy S&M film, and I told them that I would only do it if you would do it with me.” And I said, “Well, OK.” There was a meeting to go to. He never showed up at the meeting, and he never wanted anything to do with the project afterwards. He said, “I don’t know anything about directing. You just go ahead and do it.” So that’s how I met Terry and got involved with Born to Raise Hell.

Jack Fritscher: How did Terry know this guy?

Roger Earl: He was a friend of George. He had known George for years and years.

Jack Fritscher: Can we use his last name?

Roger Earl: George has passed away, so I guess it’s OK. It was Lawson, George Lawson.

Jack Fritscher: So you had those theatrical prints made, and that went on to great sales in Super-8 film, right, in the 1970s when gay mail order was beginning? I remember watching Wakefield Poole in his home office, busy stuffing Super-8 copies of Boys in the Sand into envelopes for his Irving mail-order.

Roger Earl: I guess we sold it on Super-8. You know, Terry handled all of that business. All I was interested in was the creative part. Of course, that’s why I didn’t get what I was supposed to, because I didn’t get involved.

[In West Berlin in 1989, Roger Earl told Mark Hemry and me how during pre-production in West Hollywood in 1974 he had taken out a personal loan of ten-thousand dollars from his boss, singer Dean Martin, to finance Born to Raise Hell.]

Jack Fritscher: Well, you helped launch the gay-lib 1970s as the “Golden Age of Gay Film,” because, soon after Stonewall, gay movie houses popped up in big cities and did big box office until video came out in 1981 and audiences stayed home jerking off to VHS cassettes. The majority of gay movie theaters where you could watch porn and get blown lasted little more than ten years before they were killed by the VCR and HIV.

Roger Earl: [About that decade of 1970s gay film] I want to say one thing, too, about making Born to Raise Hell and that is that I would never have made it, never had a part in it, if it hadn’t been for Fred Halsted putting out L. A. Plays Itself.

[Actor/director Fred Halsted’s 1972 American experimental film, which he began shooting in 1968, a year before Stonewall, was almost immediately accepted in the permanent collection of the New York Museum of Modern Art which for a time had the only complete original copy because censorship and marketing caused Halsted to re-cut the film several times, deleting the fisting, to please nervous distributors. L. A. Plays Itself was something new, a gay film noir of violent urban sex between Halsted and a “Texan” that ends with a montage of newspaper headlines about an S&M murder. In that way, L. A. Plays Itself is a precursor to William Friedkin’s controversial leather film, Cruising. Mistaken in his thinking that Halsted’s film was a documentary, Police Chief Ed Davis of the LAPD increased his harassment of leather bars, gay movie theaters, and, particularly, Drummer whose staff he arrested, causing Drummer to flee from LA to San Francisco.]

Jack Fritscher: In July 1975, Jeanne Barney [September 13, 1938-November 3, 2018]. published Halsted’s newest film Sextool on the cover of Drummer, issue two, and your Born to Raise Hell on the cover of issue three.

[Before the “Leather Bloomsbury Group” circling Drummer in Los Angeles was busted by the LAPD in 1976, the prima inter pares editor-in-chief of Drummer, Jeanne Barney, was a kind of straight dowager matrix to the group. She was the lifelong friend of Drummer columnist Fred Halsted and the trusted keeper of his secrets. She was the longtime friend of Roger Earl and Drummer artist Chuck Arnett who drew her. She was frenemies forever with Drummer publisher John Embry. She imagined Drummer to be a leather version of The Evergreen Review. She understood how gay films and Drummer could be symbiotic in creating the revolutionary art and eros that ignited the Golden Age of Gay Cinema in the 1970s on page and screen years before gay film/video review magazines first appeared in the 1980s. In the San Francisco Drummer Salon that followed the LA Bloomsbury Group, various filmmakers such as Wakefield Poole, the Gage Brothers, and Mikal Bales of Zeus Studio, benefitted from such hand-in-glove covers at least once. Terry LeGrand had noticed that of the many covers I shot for Drummer, including my Drummer 30 cover of his star Val Martin, four covers featured my Palm Drive Video films. In the same synergy that LeGrand and Earl had with Drummer, my Palm Drive videos were regularly featured in centerfolds and photo spreads. I liked that Drummer aggressively promoted the popularity of gay cinema in most issues, as well as in periodic Special Publications each designed as a separate movie magazine, each featuring stills from the film title: Sextool, 48 pages, 1975; Born to Raise Hell, 64 pages, 1975; and Chain Reactions, 64 pages, 1985.]

Roger Earl: Having seen L. A. Plays Itself, and having admired it, and saying, OK, it’s safe to show gay sex on screen, I no longer thought of it as something that you can’t go and do. I think Fred was truly the one who started it all, and without him I would never have done it. I really had a lot of respect for Fred.

Jack Fritscher: He liberated you.

Roger Earl: He was a friend, and I admired him very much.

Jack Fritscher: I did too. He was a pioneer [who owed much to the master underground filmmaker, Kenneth Anger, director of the quintessential S&M piss-and-blasphemy leather-biker film, Scorpio Rising (1964)].

Roger Earl: Absolutely.

Jack Fritscher: Even before I succeeded Jeanne Barney as editor of Drummer, when Barney first started, Fred was a regular columnist. He was a writer as well as a filmmaker and a great creative spirit who went on to publish his own Drummer-style magazine, Package.

Roger Earl: Exactly. I had wonderful times with him, too.

Jack Fritscher: Everyone so regretted Fred’s suicide [1941-1989] after Joey Yale [his lover and muse] died of AIDS [1949-1986]. Tell me about your wonderful times with Fred.

Roger Earl: Fred always came and bottomed for me. He was a wonderful bottom, and we just had wild, wild sexual times together.

Jack Fritscher: Halsted was a bottom? How different from his dominant image on screen. Can you describe a typical scene?

Roger Earl: We made love, that’s literally what we did.

Jack Fritscher: Lucky you, with Fred Halsted.

Roger Earl: We did that on many occasions.

Jack Fritscher: Everybody always thinks of him as the ideal top.

Roger Earl: Exactly. I’m not out to destroy this. He was a wonderful man, and a creative, terrific person. He was wonderful to play with.

Jack Fritscher: Did he like to get whipped or spanked or tit-play?

Roger Earl: Absolutely. He was game for everything.

Jack Fritscher: What about fisting? Which you so scandalously depicted in Born to Raise Hell?

[The first films to include fisting were Fred Halsted’s Sex Garage and L. A. Plays Itself, both 1972, and his Sextool, 1975. Under threats from the LAPD, Halsted was forced to cut the fisting scenes from all three films so he could screen them in Los Angeles. Because of this, LeGrand premiered Born intact in San Francisco where a politically correct someone ran from the theater making a rape accusation that its vivid handballing scene was not consensual. The “scandal” was either an urban legend that failed to credit Earl for his ability to direct actors in characterized ways that seem real, or it was a great self-generated publicity stunt by master showman Terry LeGrand who was not above hiring a stooge to create exciting or contentious “word of mouth” which is a marketing dynamic that sells tickets at the box office. In 1976, French filmmaker Jean-Étienne Siry released his gorgeous 20-minute classic Erotic Hands starring “Bill [blond-bearded], B. Dick, and Don.” “B. Dick” was Richard Trask, owner of the Wizard’s Emerald City gift shop at 1645 Market Street in San Francisco for whom I wrote and designed an advertising brochure. Trask and “Don” both played at the Slot Hotel on Folsom Street where they individually went bottoms up for me who found it an exciting challenge to surprise their insatiably experienced holiness. Erotic Hands consists of two scenes sourced from two other Siry shorts: “Entrepôt 026” aka “The Warehouse Part 1” and “Poing de Force” aka “The Warehouse Part 2.” Siry’s soundtrack to the “Poing de Force” (“Fists of Force”) section of Erotic Hands can be heard on YouTube.]

Roger Earl: Fisting. Fred and I didn’t get into all that.

Jack Fritscher: That gives me some idea of the range of you two LA filmmakers at play.

Roger Earl: But it’s wonderful memories. Very beautiful memories.

Jack Fritscher: Yes, Halsted is a saint in the S&M pantheon; but he is often ignored or distorted by politically-correct gay film historians who too often look at homomasculine cinema through a feminist lens that confuses male-sex action on screen with the non-consensual action of violence. You give a vision of male history; they give their female revision. Perhaps they do this because S&M films are not really about sex itself as much as they are about the intense male bonding and human psychology of the participants. Jeanne Barney always discerned the difference.

Roger Earl: You know, I agree with you, Jack. And that’s why [I was pleased] when they asked me to guest-edit an issue of International Leatherman [founded by Terry LeGrand who, from his twenty years of exposure in Drummer, understood fully the power of gay magazines in promoting films]. As editor, I did a whole thing on Fred, two pages, because I thought it was very important for me to testify. Like I said: Born to Raise Hell would not have happened without Fred.

[The cover of LeGrand’s International Leatherman, issue 3, January 1990, published by his Parkwood Publications, listed Roger Earl as editor, and featured Christian Dreesen on the cover shot by David Pearce on location at the Knast Bar, Berlin, June 1989; including twenty centerfold photographs from the Knast. In issue two, LeGrand wrote that he had titled his new magazine, a doppelganger for Drummer, after a fictitious magazine titled Leatherman, which was also a doppelganger for Drummer, in my Some Dance to Remember: A Memoir-Novel of San Francisco 1970-1982.]

Jack Fritscher: While Vince Trainer did your editing, did you show Fred any of the rushes?

Roger Earl: Oh yeah. Fred liked the film, admired it, and was my greatest fan. He was wonderful.

Jack Fritscher: Did you ever meet the Gage brothers whose homomasculinist films we also featured in Drummer?

Roger Earl: No.

Jack Fritscher: Few have. That’s why I wondered if you did. At Drummer, we published dozens of stills of Gage films without personally meeting Joe Gage [aka Tim Kincaid, a charming man I met at my home in 2011 when he arrived to interview me on camera for a documentary he was trying to make on David Hurles].

Roger Earl: Then I don’t feel so bad.

[As editor of Drummer seeking a hot film to follow Born to Raise Hell, I introduced into the pages of Drummer 19 (December 1977) the work of the Gage Brothers who proved a perfect fit for Drummer covers and photo spreads with their homomasculine trilogy: Kansas City Trucking Co. (1976), El Paso Wrecking Corp. (1978), and L. A. Tool and Die (1979). Like their contemporary, Roger Earl, the Gages were storytellers of episodic sex featuring the picaresque escapades of reality actors like Fred Halsted, Jack Wrangler, and the mature Richard Locke who was Drummer ’s first “Daddy” — at age 37! In content and style, the Gage mise en scene embraced technique, material, eros, and casting that were embraced in 1976 by fans of the new genre of homomasculine action movies kick-started by Halsted (1972) and Earl (1974).]

Jack Fritscher: You had the good luck to meet Val Martin.

Roger Earl: God, yes, did I ever.

Jack Fritscher: So tell me. In a sense, you and Terry are the director and producer who discovered Vallotte Martinelli [1939-1985] who was an immigrant from Brazil, a porn model, and a star in the leather bars in Los Angeles. As soon as you finished shooting Born, Fred Halsted cast him in Sextool (1975).

[Val Martin was one of the forty-two leatherfolk arrested with Drummer publisher John Embry and founding LA editor-in-chief Jeanne Barney and Roger Earl and Terry LeGrand during the raid by the LAPD on the Drummer Slave Auction, April 1976, that drove Drummer to freedom in San Francisco. Because Val became the “Face of Drummer,” I photographed him with his partner, the model Leo Stone (Bob Hyslop), for the cover of our Fourth Anniversary Issue, Drummer 30, June 1979, and for the centerfold of Drummer 31.]

Jack Fritscher: When you introduced Val to Drummer, it was a perfect fit. We put him on more covers than any other person, including the cover of the second issue publicizing Sextool, and the cover of the third issue trumpeting Born to Raise Hell. He was so popular that in 1979, John Embry, Al Shapiro, and I appointed him the first “Mr. Drummer” without even bothering to pretend he won in competition.

Roger Earl: I will tell you the truth. Leaving that first meeting with George Lawson, and driving from there, the name Born to Raise Hell came to me. I pictured the motorcycle guy with the tattoo “Born to Raise Hell.” The name came straight from that meeting. I knew that I had to have a real dynamic guy to carry this thing. Otherwise it was going to be the same old shit. So I went on my search. There was a guy who I thought would be wonderful, a Colt model, name of Ledermeister. I knew that Paul [Gerrior aka Ledermeister, April 19, 1933-January 18, 2021] hung out at some of the baths. I talked to him briefly. He really was not into the scene, although I liked his look.

Jack Fritscher: I did too. He’s iconic as a pioneer super-model in gay media.

Roger Earl: I went out to the bars, thinking, how was I going to shoot this thing? I don’t have anybody — when in walks Val! I knew he was right from the minute I saw him. I said, “You’ve got to ask him.” But I was afraid to ask him. He might smash me right through the fucking wall. Finally, I screwed up my nerve and went over to him. He was very nice to me. He said, “Why don’t you give me your card and I’ll call you tomorrow. This is not the proper place to talk about anything like this.” I gave him my card and at 10:00 the next morning he called me. He was a man of his word, a real gentleman.

Jack Fritscher: Yes, he was also supporting, so he said, his eighteen siblings back in South America, and his two children from a former marriage. We hung out in the Drummer Salon of leathermen after he moved from LA to San Francisco. Forty of my photographs of Val were published in the centerfold of Drummer [issue 31, September 1979].

Roger Earl: He was a terrific guy, nice, kind. I made a panel for Val [who died April 13, 1985] for the AIDS Memorial Quilt. I put all kinds of studding in it, the whole thing, the name. At the bottom of the panel, I put the words: “A Leatherman and a Gentleman.” That’s the way I felt about him, a true gentleman.

Jack Fritscher: He was. And he was terribly, wonderfully hot, too. It’s interesting that you considered Ledermeister because he is such a great gay porn icon from the 1960s and 1970s. He was, in fact, a lineman for a utility company [Pacific Telephone and AT&T], one of those guys you see all geared up opening manholes and climbing poles.

Roger Earl: He was just the first guy that came to mind. I needed someone for this film that was going to be a dynamic personality.

Jack Fritscher: I know his dynamism. I shot some twenty-minutes of Super-8 footage of Ledermeister in 1973 when he was out on 15th Street near the Castro doing his lineman work, wearing a tank top and sitting with his legs down inside a manhole while he stripped wire between his knees. But as you say, he wasn’t really into the scene although I often saw him at the Folsom leather bars, one time coming out of the No Name on crutches because he’d wrecked his motorcycle and broken his leg. I thought, hmmm, he’s limping. I can finally catch him. And I did. In my home. In my bed. I’ve never washed those sheets. He’s had an interesting career as a legit stage actor in San Francisco. I think you and Ledermeister would have been great together.

Roger Earl: Well, Born wouldn’t have worked [validly or realistically] without someone who was into the scene. Val was into it. He was very talented and easy to look at [playing the part of “Bearded Sadist”].

Jack Fritscher: We put Val on four Drummer covers. You are right: he was so easy to look at. Right after Born, he went on to attempt a fisting scene with Casey Donovan in Wakefield Poole’s Moving. Poole was another director featured in Drummer [issue 27, February 1979]. Who else in the cast of Born did you enjoy?

Roger Earl: I have never really had a problem with cast members. I’ve enjoyed everyone I’ve ever worked with, and the ones that I didn’t, I got rid of.

Jack Fritscher: I mean their performances on screen. Whose do you think was successful?

Roger Earl: Well, I liked that little kid, John Detour [who plays “Barroom Victim #1”] in the beginning scene in the bar. He’s the one that starts out in the bathroom and then moves onto the pool table. When he finished that and I told him thanks and that he was going to be dynamite, he said, “Is that all they’re going to do to me? I was hoping for so much more.” I said, “Just give me a couple of minutes and we’ll arrange something.” So we went on with the alligator clips and everything.

Jack Fritscher: I think that’s one of the wonderful things about S&M movies: your personal casting of guys personally committed to the scene. The actors, role-playing themselves, seem to be eager and able to go farther, faster, deeper into their real kinks than you might even hope for. In vanilla movies, the actors often seem like hired dicks, disinterested and ready to break for lunch.

Roger Earl: Well, I’ve done vanilla movies, of course. One I was on, there was this cute little “boy,” looked like he was from Arkansas, with this little wiry muscular body, and being fucked by this big bear-type guy, and all of a sudden I hear snoring. The kid is sound asleep.

Jack Fritscher: Tired? Drugged? Jaded?

[Adding to the concept of “scandal” above: It’s a problem during a shoot if questions of consent arise. It must be addressed that through no fault of Earl’s, a few in those early 1970 audiences, because they had never seen an S&M film before, were not esthetically prepared for the consensual role-playing intensity on screen which their limited experience mistook as nonconsensual violence. Few had ever witnessed fisting, which was a rather new sex practice in the 1970s. So they had no way to judge the negotiated consensuality of the on-screen fisting scene that was meant to be a thrill even as the bottom acted out his “resistance.” True players know that in a sling, with or without a camera present, the dialogue is a constant stream of yesyesnoyesnonoyeeeeesss! Born to Raise Hell is meta-cinema, like a play within a play by Jean Genet where actors play actresses playing the role of maids playing the role of their mistress who in turn plays the role of the maids playing actresses playing actors. Earl cast non-actors to play themselves as role-playing characters who are themselves. Falling through the looking glass of the screen, Born dramatizes a normal leather night’s sex play by authentic men within a fantasy film about S&M reality directed by Roger Earl. As sadomasochism came out of the closet in the 1970s with fictitious international films like The Night Porter and Salo, audiences grew into sexual literacy, and stopped freaking out like fundamentalists that a documentary director as skilled as Earl could overpower them with film verite dialogue and images that would shake their willing suspension of disbelief — which is the goal of a storyteller.]

Roger Earl: The big guy is just fucking him like crazy and he’s snoring.

Jack Fritscher: Very different from the sex excitement on your Bound sets. I remember Terry would have an authentic twosome or threesome of kinksters standing by to film their sequences, and all of them were ready and hot to trot, and were so intense that you decided not to yell “cut” when their scene ran longer than you had planned. That’s one of the reasons Bound which was pitched as three features ended up being six.

Roger Earl: You just go with it [the actors on a shoot] and get what you can and tear it apart [in post-production] when you get it home.

Jack Fritscher: Sure, if the players want to beat each other up for another hour, it’s cheaper to roll tape than it was to shoot film. Sometimes all the excitement was not on screen. Remember when we were shooting in the Knast? The long line-up of steel plates that were the floor-covering of the bar somehow got electrified from all our power cords, and the cameras and lights kept shorting and blinking. Mark and I spent much of that shoot lying on the floor aiming angles up to heroize the action, and our bodies started tingling, head to toe. Cheap thrills on Fuggerstrasse! We were all being electrocuted. And you immediately saw to everyone’s on-set safety.

Roger Earl: For me, the key to it all, the thing that I think I have the most talent at is editing. I take a lot of pride in that. I see so many films, I say to myself, why didn’t they cut that? They went right to this. Tighten this up. I see so many films where there is no rhythm. You’ve got to have a rhythm. Some of the people who do pornography don’t understand that.

Jack Fritscher: I call those people “tripod queens.” They put the actors on one side of the room and the camera on a tripod on the other side. They never move the camera, never zoom in, and basically release CCTV footage. They haven’t made a film. They made footage. They’ve just turned on the camera. Yet it sells because most people will watch shit as long as it’s new. From my thirty years in the business, I figure that consumers rarely even care that gay video could be better than it is. In fact, I think it’s ironic that gay people are supposed to be so much smarter and have such better taste than straight people, except when it comes to gay video, and we often make worse videos than they do, except for you. You have a rhythm.

Roger Earl: That’s important to me.

Jack Fritscher: You do have a good editing rhythm. Mikal Bales [1939-2012] of Zeus Studio, whose first bondage films I introduced in Drummer [issue 30, June 1979], has a rhythm, but it’s a camera rhythm, not an editing rhythm. He moves the camera around the action very nicely. He cuts differently from the way you cut because of your two completely different artistic styles, both of which suit your work.

Roger Earl: Right.

Jack Fritscher: Born to Raise Hell was your first movie. How many have you made over all?

Roger Earl: Hmmm. Probably 45. Which includes all the vanilla stuff.

[Roger Earl told Kevin Wolff in Drummer 126: “I’m doing another non-S&M film shortly. I’ve got quite a background doing porno films. Non S&M films are always scripted. S&M porno films are unscripted for me. You can do a light script, but I prefer to do segment things and just let guys do their own thing without me telling them, ‘You’re playing a part.’ …Once I give them a character, and have them play a part…, it takes away from their real self. I think that’s more important in an S&M type thing….Maybe I should try scripting an S&M film sometime. I feel I get more out of people by not doing it.”]

Jack Fritscher: I think highly of your Gayracula, Men of the Midway, and Chain Reactions which was also published as a special Drummer photo book. You were at your production peak by the close of the 1980s. So I was delighted that Terry, because he had liked how Mark and I, two cameramen shooting with matching style, invited us to film with you at the height of your career in 1989. I know that when we all met on the boat in Amsterdam that Terry and I were celebrating our June birthdays. How about you?

Roger Earl: I was born in January 1939. Aquarius.

Jack Fritscher: I’m June. Gemini. 1939. Where were you born?

Roger Earl: A town called Barstow, California. In the Mojave Desert.

Jack Fritscher: What was it like growing up in Barstow?

Roger Earl: I grew up in Ludlow, a town of thirty-five people, fifty miles from Barstow [East, on I-40], but I went to school in Barstow. It was wonderful growing up where I did. I was the only child in a town of thirty-five people, spoiled rotten not only by my parents but by the entire town. I could do no wrong and they couldn’t do enough for me. My dad had a truck stop, garage, motel, café, all of that. I started in on [sex with] truck drivers when I was seven years old.

[For twenty years, beginning in the 1940s, Roger’s parents, Earl and Lillian Warnix, ran the popular Art Deco Streamline-Moderne Ludlow Cafe and Union 76 gas station in the Mojave Desert on the legendary Route 66 in Ludlow, California. When the incoming Interstate 40, known as the “Needles Highway,” bypassed the town in 1964, they sold their historic building which lasted several more years as a business before it burned down into ruins that remain in the ghost town where Roger once greeted incoming traffic.]

Jack Fritscher: You grew up living Halsted’s Sex Garage.

Roger Earl: I was well known up and down the line. They would come in and want to know if there was a kid here named Roger. And I would take on the truck drivers. If I didn’t like the looks of them, I’d say, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Jack Fritscher: How did it dawn on you at the age of seven to do this?

Roger Earl: I was a horny little bastard, I was very sexual at the age of seven. I had an uncle who was an incredible looking man. He was just beautiful, big muscles, hairy chest, and all that. Of course, it is very hot in the desert around Barstow and he ran around with his shirt off all the time. When I was a kid, I ran around in my underwear, just a pair of jockey shorts. He used to pick me up and hold me in his arms and, wow! the electricity would just fly.

Jack Fritscher: Was he aware you were turned on?

Roger Earl: I don’t think so.

Jack Fritscher: The point I’m getting to is, most people instinctively know that if someone has sex with a seven-year-old boy, the boy is being abused.

Roger Earl: I know. That’s the dumbest thing in the world. I was a real aggressor like you wouldn’t believe.

Jack Fritscher: Mark was the same at about the same age. He knew what he wanted and went out and got it. Both of you seem to have understood consent at an early age. If that’s even possible.

Roger Earl: You couldn’t blame anybody but me. I guarantee you.

Jack Fritscher: Did anybody else in the town find out about this?

Roger Earl: No, and let me tell you honestly, Jack, I could have sucked dick right in the middle of Highway 66 and nobody would have believed it because I was the perfect person. I could do no wrong. I was the best little boy in the whole wide world. It was one of those situations where I had the best of everything.

Jack Fritscher: So you went down on these guys and sucked them?

Roger Earl: Sure.

Jack Fritscher: What about anal sex, anything like that until you were a teenager?

Roger Earl: I did, yes. They fucked me. When I got to be seventeen or eighteen, I suddenly decided that I didn’t like that at all anymore and basically haven’t done it since.

Jack Fritscher: How old were these guys? All different ages?

Roger Earl: Anywhere from their twenties to late forties or fifties. There were some fifty-year-old guys that were incredible.

Jack Fritscher: Most people, Roger, will have difficulty understanding this fact of your own psychology.

Roger Earl: It was a wonderful experience. And, of course, the movies! Once in a while I would get to go to Barstow to the movies, and I would get all worked up, especially if it was a Tyrone Power movie where he was tied up in a dungeon and put on the rack. It drove me right up the fucking wall, and I’m talking seven-eight years old.

Jack Fritscher: Was your family religious?

Roger Earl: No. There was no church in Ludlow. I mean they were religious, but not [practicing] when they came to Ludlow.

Jack Fritscher: I was wondering if your sadomasochistic interests were fueled by religious tales, like heroic Christian martyrs tortured by gladiators in the Roman Coliseum. Or something like that.

Roger Earl: I never went to church. Religion has never been part of my life.

Jack Fritscher: That probably accounts for the guilt-free purity of your movies. What is your second favorite film after Born to Raise Hell?

Roger Earl: There are a few. I definitely like Like Moths to a Flame because that was the first one I did with Christian Dreesen. Christian is very special to me just like Val was.

Jack Fritscher: Tell me how you met him. He was a refugee who had somehow escaped from East Germany.

Roger Earl: Strangely enough, I saw him in one of those little European S&M books. I think it was called Mr. S&M or something like that [actually TOY], in one of the ads. Terry and I had already met one guy in England, the guy that owns Fetters [custom leather shop] in London…

Jack Fritscher: Maurice Stewart known also as “Jim Stewart”? [British stage-and-screen actor and director, James Maurice Stewart-Addison, 1932-2012; not American leather author and photographer Jim Stewart, 1942-2018, who wrote the memoir Folsom Street Blues.] He founded Fetters. He owns it. I’ve known him since we met in swinging London in 1969 when we were having sex at his home and he was so proud of the leather toys he was just then inventing before he went into business. He introduced me to his circle of leather bikers who hung out at the Coleherne bar, out on Old Brompton Road.

Roger Earl: Yes. That Jim: Maurice. He designed and built the S&M equipment used in the film. He was friends with these other [leather] people. Anyway, we were going to see Stewart, and we talked to these two other guys, David and John, about doing a film. David [Pearce] was John’s, mmm, I don’t know what. He lived with John [my friend John Howe], but I never could figure out if they were lovers or not.

Jack Fritscher: David lived on the dole and depended on the kindness of strangers. When you introduced us to him in Amsterdam, he held out his arms to Mark and me and said, “Are you the gentlemen I’ve been expecting?” We three became friends until David disappeared during the AIDS crisis in the early 1990s. David was as great a painter as he was a photographer, and he knew everyone who was anyone in London.

Roger Earl: Yes, and in pursuit of Christian, I was going on and on about this gorgeous guy in this book, and I showed his picture to David who Terry hired to be our still photographer for Dungeons, and David said, “Well, I took the picture. That’s Christian.” I said, “Well, call him, damn it! I want him in my movie.” And that’s how we met Christian.

Jack Fritscher: So you flew him in from West Germany to London.

Roger Earl: Exactly. He worked with John [Howe] in the first film, Like Moths to a Flame. Down in John’s little basement area.

Jack Fritscher: John’s done some interesting work as an extra in a number of films shot in England, Hollywood-type movies. When the Operation Spanner scandal happened in England in 1987, what did you think of that witch-hunt that started with seizure of a gay S&M video the Manchester cops thought was real torture leading to a gay snuff film? [The fundamentalist British court ruled that an adult person does not have the legal right to consent to receiving what they considered bodily harm in BDSM play.] One of your actors, Mr. Sebastian [Alan Oversby, 1933-1996, British pioneer body piercing and tattoo artist], was one of the sixteen men arrested. Refusing to consider the issue of consent, the judge sentenced him to a fifteen months suspended sentence for performing genital piercings on willing clients.

Roger Earl: I kept thinking, I hope to God the criminalizing of S&M has nothing to do with us. I was afraid it did, and then later on I found out it [Spanner] didn’t have anything to do with us.

Jack Fritscher: Still, that fundamentalist wave of new British and American censorship as the 1980s became the 1990s was very threatening to us all. If you recall, because Mark had a lifelong career within the U.S. Government, and because I was so affected by the censorship against the photographs of my dear friend Robert Mapplethorpe, we asked Terry to remove our credit as cameramen for caution against legal reprisals because of the very heavy S&M sex in Bound. The hot footage we shot in Europe seemed dangerous in the States. So the credits for the videos in the Bound six-pack sometimes list us and sometimes do not. That ambiguity is not unusual in the history of gay cinema where legal anxieties often impact the credits of producers, cast, and crew.

Roger Earl: Yes. As you know, movies are copied and bootlegged all over, but we never set up any European distribution of any of these films. So we were safe. We distributed our Marathon films only in the United States, although I am sure our titles were copied and sold by pirates all over the world.

Jack Fritscher: These London leathermen were convicted of performing consensual S&M acts on themselves and you were shooting consensual stuff. I think that society in Europe, England in particular, as well as in the U.S. has grown more uptight with the rise of fundamentalist religion of the kind that caused [the right-wing Republican] Jesse Helms to attack Robert Mapplethorpe for his leather photographs on the floor of the United States Senate in 1989, the same summer you and I were together shooting Bound for Europe. There was a wonderful window still open in the culture war when you shot Dungeons in 1988, but that window was closing when we shot Bound. That last summer of that decade when we went to West Berlin with you was an ironic pivot in gay culture because both Spanner and Helms were shutting down freedom of personal and artistic expression at the same moment the Berlin Wall came down, opening up freedom. Remember how repugnant those hard female East German customs guards were who tore through our suitcases and cameras when our group of gay men stood nervously in line to board our flight over Communist East Germany into West Berlin, which had a limit on its population? One American had to exit West Berlin before another could enter. Five months later the wall came down. Shooting porn in that city that summer, surrounded by Communists, was like something defiant Christopher (“I am a Camera”) Isherwood might have done in the Weimar Republic before World War II. It was a magical time and a wonderful time. And a dangerous time.

Roger Earl: Yes it was, and I am just so thankful that we were there then.

Jack Fritscher: Now, eight years later with Reunification, the mood of Berlin has changed. A German shoot now would be less of a political act.

Roger Earl: And so many of our friends are gone now that were there then. The guys that owned the Connection bar.

Jack Fritscher: So many gone…. After everyone’s cult favorite, Born to Raise Hell, what is your next personal favorite film? In 1980, six years after you shot Born, you shot your film, Rear Admiral, with Fred Halsted’s lover Joey Yale, followed by Gayracula (1983). It’s seriously hot porn, but has comic elements, and camp in character names like the “Marquis de Suede.” I think that Gayracula’s fixation on blood at the start of the AIDS epidemic makes it a timely psychological study amidst the terrific sex.

Roger Earl: I’ll tell you, Gayracula was a fun film. I was crazy about Tim Kramer. Such a sweet, lovely man.

Jack Fritscher: A luscious All-American blond. When he’s bitten on the neck, it ain’t a normal hickey.

Roger Earl: Another film that I really enjoyed doing was Chain Reactions.

Jack Fritscher: A terrific film. Drummer published a great review of Chain Reactions with eleven photos in issue 78, with cover copy asking the inevitable question: “Sneak Preview: Is the New Chain Reactions a Sequel to Born to Raise Hell?” Drummer followed that feature with the Drummer special Chain Reactions photo book of sixty-four pages. There’s that synergy again between Drummer and film. The review, which I have at hand, mentions you and Terry hosting Drummer with Ken Bergquist (Mr. Drummer 1984, first-runner-up) at your home “where Roger whipped out over a thousand photographs of their new film, Chain Reactions, which was almost finished.” You struck a deal to cast Bergquist in the final motorcycle orgy scene which was shot at the bar “‘Chains,” which was made over from the [bar] the “Pits” in Los Angeles, much as Born to Raise Hell was shot at the old “Truck Stop” [bar] out in the San Fernando Valley. And what a compliment Drummer pays you! Your name becomes a brand name in the line: “The action is uniquely ‘Roger Earl,’ very leather with a flair that few filmmakers can approach.”

Roger Earl: I understand that today Chain Reactions has unfortunately been chopped up by distributors.

Jack Fritscher: That film had orgy sex, spankings, slings, and enemas. Was that Daniel Holt that you tied up in the spider-web? For Bound, I remember how you had the “Dutch Master” Harry Ros spend hours before our shoot tying a slave into a rope spider web.

Roger Earl: That was Dwan tied up in the Chain Reactions web. I designed the whole smoky thing with the candle wax and all that. Those were fun scenes that I thought turned out sort of artsy-fartsy and were still erotic. That one kid here in LA who made artsy videos and just died…

Jack Fritscher: Bad Brad. Nice kid. [Brad Braverman, 1961-1996, porn star and director, invoked Roger Earl’s Gayracula in his feature video Disconnected (1992) with its vampire sequences.]

Roger Earl: Yes, him. His videos are artsy, but I don’t find them erotic.

Jack Fritscher: I agree. I interviewed him last year right before he died and I thought he was way more of a film editor than he was a filmmaker. He was a stylist with little content. It was unfortunate that he died so young because he might have eventually learned how to use both content and style to compose a film. I doubt if anyone could cum to his work, which was like a soap or car commercial, very MTV.

Roger Earl: That’s the key to me. If I can’t get off on it, it’s a waste of my time.

Jack Fritscher: I told Bad Brad nobody ever shot their load to a special effect on screen.

Roger Earl: Never will.

Jack Fritscher: CGI special effects. Salad-shooter editing. Not hot. The best art conceals itself to help the audience suspend their disbelief. Overt technology calls attention to itself and distracts sexual heat. It’s often the ruination of eros when people get too “high tech.” My friend, the San Francisco filmmaker Michael Goodwin [1937-2006, founder of “Goodjac Productions”] who does the Goodjac Chronicles also gets too artsy. He yearns to be an artist, but he should make art films on one side and erotic films on the other, and not mix the two. Art school is one thing. In the real world, art and sex rarely seem to mix because horndog viewers are voyeurs who don’t want to start thinking while they are masturbating to forget the workday they spent thinking about real life. Robert Mapplethorpe, in many people’s minds, mixed style and content together for perfect moments that are maybe intellectual and esthetic, but not hot moments. He was more of a stylist. I doubt anybody has ever jerked off to a Mapplethorpe photograph.

Roger Earl: He never did film or video, did he?

Jack Fritscher: Yes. And he screened his rushes for me. Shortly after he and I met, he directed Patti Smith in Still Moving [10 minutes, 1978] while Lisa Rinzler ran the 16mm camera for him as we did for you. He also directed bodybuilder Lisa Lyon in Lady [1984]. He was a static artist in search of the perfect moment, the perfect film “still,” not the perfect “motion picture.” He was a master of “still life” art whether it was a flower, a fetish, or a face. Roger, there is nothing “still life” about your athletic films. Your guys look like sex-action heroes: sweaty hot dudes with some tread on their nipples like Christian Dreesen escaping from the East German Stasi, and Mr. Sebastian [1933-1996] working with filmmaker Fakir Musafar [1930-2018], the founder of the modern primitive movement, in creating the body modification scene.

Roger Earl: What a wonderful person Sebastian was. Another reason that I’m crazy about Like Moths to a Flame.

Jack Fritscher: Do you know that when Sebastian died eleven months ago, his obituary made international news in the New York Times and the UK Independent?

Roger Earl: Really? I was not aware of it. How wonderful.

Jack Fritscher: Mark and I were on a plane to Paris and found it. I thought, well, here’s a nice little connection. It was like “Six Degrees of Roger Earl,” and there’s Mr. Sebastian in the New York Times.

Roger Earl: I thought you were going to tell me that he and his tattoos had been made into a lampshade.

Jack Fritscher: He was one of the most pierced, tattooed persons in the world. What was he like personally?

Roger Earl: Charming, sweet, adorable, loving. I was just crazy about him. You couldn’t help it. He was a very vulnerable man too.

Jack Fritscher: But a heavy duty S&M player?

Roger Earl: Not so much, just really into all this clinical piercing and tattoos.

Jack Fritscher: More of a real practitioner of body modification than an erotic exhibitionist?

Roger Earl: Yes. But for me his scene worked in the film.

[Roger Earl told Kevin Wolff in Drummer 126: “Mr. Sebastian in Like Moths to a Flame…We shot the whole thing [the Mr. Sebastian sequence] in his [tattoo] studio, because he insisted. See, I wanted to shoot it somewhere else, in kind of a scene thing, but he said, ‘In my studio I know there can never be an infection, and for sanitary reasons I will not do this outside the studio.’ The minute he told me that, I said, ‘There’s no more discussion. You’re absolutely right.’” Earl told former Drummer publisher John Embry, who had cloned his new magazine, Manifest Reader, out of Drummer, that other scenes in Moths were shot in the cellar of “Expatiations of London” and “in Germany.” Men with No Name was shot in the cellar of RoB of Amsterdam. “Time was running out…We knew we had to go back home. That was how series two, Bound for Europe, came about.” Manifest Reader, 33, 1997]

Jack Fritscher: I see gay history listing you as a filmmaker and a videographer, but I’ve never seen you called what I would like to call you: a documentarian. You search out and cast people who are the real thing and then give them permission to do the real thing in front of your camera. You told Drummer: “I work with men who are into the scene one-hundred percent.” Plus, I know from experience that the “Roger Earl camera” is a power tool. The presence of the camera encourages real players to dig deep to represent their scene with an intensity greater than it might be without the motivation of the camera which they are very aware documents them and their trip forever.

Roger Earl: At this point, Jack, I have to tell you I give a thousand percent credit to my partner and friend, Terry LeGrand, because without him — he’s the one who has the guts to go out and really get these people. I say I want this one and he gets him. We work wonderfully together.

Jack Fritscher: Indeed you do. I’ve seen Terry in action interviewing new talent to populate your set. In Europe, while you were directing one scene and thinking about the next scene, Terry was out convincing very hot, but camera-shy, tops and bottoms to come let it all hang out on your set. How many films have you worked on together?

Roger Earl: Everything I’ve done.

Jack Fritscher: So you and Terry are business partners, not lovers. Not ever?

Roger Earl: We are not lovers.

Jack Fritscher: Do you have a lover?

Roger Earl: Not now.

Jack Fritscher: Have you had lovers?

Roger Earl: I have had.

Jack Fritscher: How many? Were they domestic partners or just lovers?

Roger Earl: One was somebody that I lived with for five or six years, until he got so jealous of me that he had to leave.

Jack Fritscher: Turning again to hired talent. What is your opinion of that British David Pearce as a photographer? He shot the stills for all three titles of Dungeons of Europe and five of the six titles of Bound for Europe, except The Argos Session which I shot.

Roger Earl: Quite a lot of his work was good, and some of it I was disappointed in; but everything is not going to be a masterpiece.

Jack Fritscher: Drummer certainly relished his photos which have become famous.

Roger Earl: For what I needed, he did some wonderful stuff. He was fine. Didn’t he come and stay with you and Mark for awhile?

Jack Fritscher: The first time he came to our home, he stayed for three weeks and painted quite a wonderful oil painting of Mark and me. That was 1990.

Roger Earl: He was a very talented artist.

Jack Fritscher: In 1993, he asked to come visit us again, and we looked forward to seeing him. I’m sad to tell you that he, like so many others, had been driven to deep depression by the AIDS epidemic because he thought he might be positive. He was living on the dole and complaining he’d been kicked in the teeth by Margaret Thatcher. He was a mess. He had missed his flight from Heathrow because he and his leather traveling companion were too stoned to board. So he showed up loaded a day late, actually at 4 AM, with his drugged-out friend he had not told us existed. Obviously unwashed for weeks, the two of them were circling the drain. It was a sad and long way from the starry night you introduced us in Amsterdam, because David Pearce had become a beloved friend and was an extraordinary artist with brush and camera. He was so demanding, tweaked, unwashed, and far gone that within a day, we asked them to leave. They were not the gentlemen we were expecting.

Roger Earl: So sad, indeed. AIDS has robbed us all of so much.

Jack Fritscher: Swept away. All the more reason to look at the documentary qualities in your films. In a sense, most of the people whom you’ve shot would have disappeared into history if you hadn’t shot them because many of them have died in this unfortunate plague and the only thing they left behind, the only creative thing that people will even pay attention to, are the images that you’ve captured of them on film. Fred and Val — your entire casts — still live on screen. I think that’s a very significant thing you’ve done. You couldn’t have known that you were doing that on such a scale, making films for the ages, when you shot Born to Raise Hell, but it turned out that way. When did you sense that Born was a true phenomenon? When you hired Val Martin? While you were shooting it?

Roger Earl: Not while I was shooting it. It was after it had been screened. The way it was received. This being my first movie. I was happy with it. To me it wasn’t erotic because I had looked at it two thousand times before the damn thing was edited and in the can. So at that point it wasn’t erotic for me, which worried me very much. I thought, Jesus, nobody will find it erotic because I can’t find it erotic. It’s full of the kind of things I love, but why can’t I find it erotic?

Jack Fritscher: I can’t find the films I shoot erotic either.

Roger Earl: You look at it over and over so many times.

Jack Fritscher: A filmmaker has so many camera and editing decisions to make, the footage becomes a mathematical thing that you have viewed so often that, while you work professionally to edit it to increase its heat for viewers, it loses its personal heat for you.

Roger Earl: Exactly, and Born was definitely not erotic to me.

Jack Fritscher: If you could find the actual date of the premiere at that Powell Street theater, I’d appreciate it because that was the day you and I first met.

Roger Earl: You know, I don’t have the foggiest idea how even to research that, Jack. I don’t even know when Born to Raise Hell was first shown in LA. I have no concept.

Jack Fritscher: Maybe Terry would know.

Roger Earl: I’ll ask Terry if he can figure it out. If he has any records.

Jack Fritscher: It was in June, I think, of 1975. At that time, I was already writing about gay history and I thought, God, gay liberation is wonderful because we’re going to a real movie theater, not a porn theater, to see an S&M movie. So [my then partner, Drummer photographer] David Sparrow and I went to the premiere. The crowd loved it.

Roger Earl: We got a very good response, and I certainly was thrilled by that.

Jack Fritscher: Did that get reviewed, do you remember, in the San Francisco Chronicle or Examiner?

Roger Earl: It got reviewed in Variety.

Jack Fritscher: Variety is the show biz bible. It should have it listed. Variety reviewed Wakefield Poole’s Boys in the Sand [1971] and Fred Halsted’s L. A. Plays Itself [1972]. Do you have the Variety review?

Roger Earl: I think I do somewhere. I’ll have to look for it. I have a scrapbook somewhere.

Jack Fritscher: If you could make a copy of that for me, I’d love it.

Roger Earl: Variety liked it.

Jack Fritscher: Great. What are your plans right now for the future of your film career?

Roger Earl: I don’t really know. When I was in San Francisco, I spoke to Beardog Hoffman and Joseph Bean, and I might make some films for them [Brush Creek Studio who bought International Leatherman from LeGrand]. I don’t know if that will come to pass. I’m one of those people who doesn’t want somebody else controlling their creativity or anything like that. If they can live with that or not, I don’t know.

Jack Fritscher: Then also, you have to sort who owns the rights to what you shoot.

Roger Earl: It’s the kind of thing where I have to draw up a proposal which I haven’t had time to do. If they like it, fine. If they don’t, then I’m not interested. That’s just the way I am. My way or no way. Not everybody is going to accept that, let’s face it. Good old Terry would always accept it.

Jack Fritscher: Because you two are a famous couple like Rogers and Hammerstein, Kander and Ebb, Mickey and Judy. You work together to put on a show.

Roger Earl: Terry and I each did our own thing and did it well.

Jack Fritscher: And the two of you produced magazines as well?

Roger Earl: No. Terry did the magazines. I was allowed to edit that one issue of International Leatherman. He begged me to, and I finally said OK. It was the best issue they ever did.

Jack Fritscher: I’m on the cover of the current issue [April/May 1997]. I mean, it’s not actually me, but a photograph I took of Chris Duffy during one of my Palm Drive Video shoots.

Roger Earl: I thought you were on the cover.

Jack Fritscher: No, Turning sixty, I’m a bit past being on the covers of gay magazines. It’s my shot of Chris Duffy, Mr. America, on the cover.

Roger Earl: I keep running across this photo of you naked, with rubber boots on?

Jack Fritscher: Hmmm. Yes. Photos like that exist in the Drummer archives, but have they escaped?

Roger Earl: I’ll have to look it up. I think I have it on my computer. I think I pulled it off the Internet.

Jack Fritscher: Really. Oh. I’ve been turned into a screen saver.

Roger Earl: Indeed.

Jack Fritscher: Is there anything you would like to say about your career or your life? This is an opportunity to do that.

Roger Earl: I must say I’m always a happy person, and I’ve had a happy life, and have experienced some of the most wonderful things through my film career and through my other career. So am I a happy person? Damn right, I am. I don’t know what else to say. I’m not good at expressing myself, in talking. I express myself in film.

Jack Fritscher: You’re doing fine. Let’s wind this up with your birth date again and some heritage.

Roger Earl: January 27, 1939.

Jack Fritscher: You’re six months older than I am. You’re my elder.

Roger Earl: I’m usually everybody’s elder.

Jack Fritscher: Are you Scottish?

Roger Earl: No, maybe a little bit, but I’m German and everything else. A mongrel.

Jack Fritscher: From Barstow. The cocksucking boy from Barstow. I always think of you rather as the royal “Roger, Earl of Warnix.” Where did “Earl” come from?

Roger Earl: It was my father’s name. His first name.

Jack Fritscher: And “Roger”?

Roger Earl: Old family name. Part of my family had a last name of Rogers.

Jack Fritscher: OK. Outside of your dick size, I don’t need anything else right now.

Roger Earl: Well, we ain’t going to give that.

Jack Fritscher: Good answer. I would like to thank you very much.

Roger Earl: My pleasure.

Jack Fritscher: As a journalist, may I say you give good interview.

Roger Earl: Well, you just have to go with the flow of my words because I don’t express myself well, Jack.

Jack Fritscher: Roger, you express yourself just fine. Thank you very much for this, and for the opportunity you gave Mark and me to be cameramen on your films.

Roger Earl: Say hello to Mark. You guys take care.