FEATURE ARTICLE

by Jack Fritscher

How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

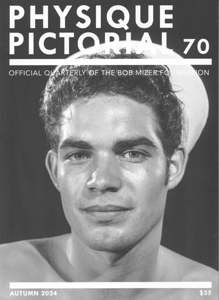

PHYSIQUE PICTORIAL

No 70 Autumn 2024

FEATURE ARTICLE

by Jack Fritscher

How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

PHYSIQUE PICTORIAL

No 70 Autumn 2024

REX REQUIEM

by Jack Fritscher, PhD

Rex aka Rex West, the controversial international icon whose genius drawings disrupted the vanilla gay world in the 1970s, was born in Connecticut February 5, 1944, and died in self-imposed exile from America in Amsterdam at the end of March 2024. He was 80. He was the last of his peers including Tom of Finland, Robert Mapplethorpe, Bob Mizer, and David “Old Reliable” Hurles. With his Rapidograph pen, he dotted out hundreds of pointillist images of masculine-identified blue-collar men for his drawings, books, T-shirts, and tattoos. A Rex drawing is as identifiable as a Tom of Finland or a Keith Haring. His style was known before anyone knew his identity.

Diagnosed with autism as an adopted toddler and bullied as a schoolboy working on a tobacco farm with field hands, he was a beat-punk runaway to the West Village where at sixteen in 1960 he learned about “gay sex from straight men in sleazy Bowery bars.”

“I bought a train ticket to New York,” he said, “where on 42nd Street I found magazines in adult bookstores where I first saw what I didn’t know then were the drawings of Tom of Finland and the photos of Bob Mizer. That convinced me New York City was my destiny.”

Unlike publicity hounds Warhol and Mapplethorpe, he kept a low profile as a typist and a house artist for the Mafia who code-named him “Rex.” From 1976-1985, he illustrated gay novels for a Mafia publisher and was marketing art director for the mob-owned Mineshaft bar that he made world famous with his Mineshaft posters and Mineshaft T-shirts worn by thousands of men including popstars like Freddie Mercury. For forty years, he supported himself with his mail-order business, Drawings by Rex.

When Drummer reviewed the Mineshaft in 1977, it focused on the media power of Rex as an influencer citing the Mineshaft as his greatest creation. “The Mineshaft Is a Fantasy by Rex. The essence of the Mineshaft is found in page after page of Rex’s drawings in his portfolios Männespielen and Icons. If you get off on Rex, you’ll like the Mineshaft and you’ll understand why the Mineshaft chose him to design its 1978 poster and T-shirt. Rex epitomizes the concept of the Mineshaft Man.”

“My drawings define who I became,” he said of his closeted personal life. “There are no other ‘truths’ out there.”

Like Tom, Mapplethorpe, and Mizer, Rex’s main accomplishment was forcing the transformation of twentieth-century male pornography into acceptance as twenty-first century art.

“Drawing the sex comes easy,” he said in a 1995 interview. “I spend more time drawing the lampshade lighting the sex. Some drawings I do sixty or seventy times. I figure I average out working at $5.37 an hour.”

When asked “As an artist, are you a pornographer?,” he said, “I certainly hope so! Otherwise I’ve got a lot of explaining to do to myself as to where the 1970s went. I want to draw pictures nobody has seen before.”

One day at lunch on Castro Street, Robert asked Rex, “How do you do it? How do you make your drawings so erotic?” Rex just grinned at his frenemy and said, “More pasta?”

Rex was a modernist trying to make gay art new by changing the gay gaze. The A-gay establishment hated him. On July 7, 1975, a gay journalist at the Village Voice attacked him as a “Naziphile” for drawing S&M pictures of leathersex and saying “The greatest S&M trip in history was the Nazis.” Like Tom of Finland, Rex had a fetish for Nazi uniforms but not Nazi politics.

The surprise attack caused an existential PTSD that made him distrust the gay press for the rest of his life. Unloved in New York, he visited San Francisco where Drummer, the gender-identity magazine, gave him his first cover, and Oscar Streaker Robert Opel hosted his first exhibit, Rex Originals, at the Fey-Wey gallery in 1978.

In 1980, to change his luck he moved to San Francisco to set up his studio, “RexWerk,” fifty feet off Folsom Street on March 1, three months before “Gay Cancer” hit the headlines on July 3, just one week before the worst fire in San Francisco since the 1906 earthquake destroyed his home and all his drawings on July 7.

Traumatized again, he hid out in a flophouse room above the Rainbow Cattle Company bar, 199 Valencia Street, and stopped drawing for a year. “My work is very dependent on my moods.” When the money from a Mineshaft fund-raiser dried up, he hired out for years as an anonymous day-laborer painting Victorian house interiors. In 1986, returning to society with new work, he published his newest drawing “Phoenix” signifying his resurrection on the cover of his first hard-cover book, Rexwerk, published in Paris.

His drawings are culturally important to class and gender identity because they expose the underground world of gay men dealing erotically with masculine isolation and existential loneliness.

In San Francisco, the skid-row Tenderloin neighborhood was right up his alley. So from 1990 until he fled to Amsterdam because of American politics in 2011, he lived and kept a studio above the “olde curiosity shop,” the vintage erotica store, The Magazine, at 920 Larkin Street which became the home of the Bob Mizer Foundation in 2016.

In the Tenderloin, he dot-dot-dotted his dudes into existence as veterans of rites and rituals in factories, prisons, and the military. His men, modeled on the Marlboro man, are a roll call of rough bromance in gorgeous rooms of falling plaster, naked bulbs, beer cans, cigarette packs, knives, syringes, condoms, and guns in the glove box of a pickup truck.

For fifty years, he sold safe-sex orgasms to middle-class gay men with a fetish for slumming with low-class working men.

Collectors appreciate that Rex produced high-resolution photographs of his work on slick Kodak stock and in portfolios like Männespielen, Icons, Sex-Freak Circus, and his radioactive Peter Pan that was his Lord of the Flies.

Coming to bury Caesar, not to praise him, it’s painful to write that some choose to cancel Rex while honoring his art. Just as there is no Saint Mapplethorpe, there is no Saint Rex. He admired Donald Trump and Ayn Rand. He was, by dozens of eyewitness accounts, a jealous man who trashed nearly everyone he ever worked with. In 1994, the Leslie-Lohman Museum labeled him “Persona Non Grata.”

When the Bar Area Reporter warned readers that “Rex doesn’t care what you think about smoking, IV drug use, pederasty, or bestiality,” the artist more censored than Mapplethorpe said, “Censorship is a desecration of the artist's idea.”

“I don’t deal with people. I don’t deal with critics,” Rex said invoking Robert’s signature line: ‘If you don’t like these pictures, maybe you’re not as avant-garde as you think.” © 2024 Jack Fritscher

—Excerpt from the forthcoming 2024 book, Inventing the Gay Gaze: Rex, Peter Berlin, Crawford Barton, and Arthur Tress which can be read free at DrummerArchives.com